Tri-County Genealogical Society

"because the trail is here"

Phillips - Lee - Monroe Counties in Eastern Arkansas

PHILLIPS COUNTY

HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Volume 7

MARCH, 1969

Number 2

Published by

The Phillips County Historical Society

The Phillips County Historical Society supplies the Quarterly to its members. Membership is open to anyone interested in Phillips County history. Annual membership dues are $3.50 for a regular membership and $5.00 for a sustaining membership. Single copies of the Quarterly are $1.00. Quarterlies are mailed to members.

Neither the Editors nor the Phillips County Historical Society assume any responsibility for statements made by contributors.

Dues are payable to Miss Bessie McRee, Membership Chairman, P. O. Box 629, Helena, Arkansas 72342.

Meetings are held in September, January, and May, on the fourth Sunday in the month, at 3:00 P. M., at the Phillips County Museum.

i

PHILLIPS COUNTY

HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Volume 7

March, 1969

Number 2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Membership Roster

Dr. Theodoric Clay Linthicum

by Capt. Theodoric Clay Linthicum

Martial Spirit Ablaze

Indian Mounds in Phillips County

by Louise M. Griffin

Lieutenant Hornor Promoted

The Diary of Fred B. Sheldon: Part II

Helena at Camp Dodge

The St. Francis River: An Early Host

by Dale P. Kirkman

The Settlements

More Recollections of Central Church

by Mary G. Sayle

Back on the Farm

by Carolyn R. Cunningham

ii

ADDITIONAL MEMBERS

| James V. Belsha* | Phoenix, Arizona |

| Mrs. Herbert Hill | Helena |

| Tap Hornor* | Little Rock, Arkansas |

| Capt. T. C. Linthicum | Branson, Missouri |

| Jim McRee, Jr. | University, Mississippi |

| Mrs. Floyd Rutherford | Helena |

* Sustaining

In the last issue of the Quarterly, in the article on Mattie Thweatt Dube, artist from Phillips County, an appeal was made as to the whereabouts of any more of Mrs. Dube's paintings. In addition to the five oil paintings described in the article, another one of Mrs. Dube's paintings has been "discovered" in a Helena home.

Mrs. John Ike Moore has one of Mrs. Dube's paintings in her home at 527 South Biscoe. Mrs. Moore said the painting was in the house when she came to Helena as a bride in 1917. This was the home of Judge and Mrs. John Ike Moore, Sr. at that time. The painting was damaged when the house caught fire about 1925. Now Mrs. Moore has the painting on her back porch.

The oil painting is a still life. In the painting are a wine glass holding a dark red wine, five whole lemons and one half lemon against a dark drapery. The ornate gold frame is diamond-shaped with the picture obviously painted to go in this particular frame. In the right hand point of the picture are the initials M and T, superimposed on one another. The painting owned by Mrs. Tom Faust has this same marking.

Dues for the membership year of 1969-1970 are payable May 1, 1969

1

DR. THEODORIC CLAY LINTHICUM

by

Captain Theodoric Clay Linthicum, U. S. N. (ret.)

Dr. Theodoric Clay Linthicum, the third child of Dr. Daniel Anthony Linthicum and Phoebe Clay (Johnson) Linthicum was born on March 25, 1852 near Henderson, Kentucky. His childhood was spent in and around Henderson where he attended such schools as were provided at the time. He, as a boy, worked in the tobacco fields belonging to his father and others. His early life seems to have been the Spartan life of the average boy of the times and location. When he was two years old, his older brother, two years his senior, and Herman by name died. One sister, Blanche, remained in the now family of two children.

Why he was named Theodoric is not completely clear to me although my great grandmother (his mother) told me a number of stories about it over the years. One of these was to the effect that a friend Mrs. Porter, the wife of Admiral D. D. Porter, USN, said he was named for her son Theodoric Porter. This son graduated from the United States Naval Academy in the class of 1870. Theodoric Porter's diploma hangs in Dahlgren Hall, the Drill Hall and Ordnance Building at the Naval Academy. This Porter retired as a Commodore and died in Washington in 1920.

The story I have always thought most likely and the one I like best was that he was named for Theodoric the Great, the king of the Visigoths, who sacked Rome in the sixth century AD. The Clay part of the name comes from my great great grandmother who was originally a Clay and a cousin of Henry Clay. My grandfather for a long time for some reason insisted the spelling was THEODRIC which is of course incorrect but that is perhaps the reason his name is so spelled in Mrs. Badger's book on the Linthicum Genealogy. I restored the other 'o' and use the correct spelling THEODORIC and shall so refer to my grandfather.

During the Civil War he was a boy, ten to fourteen years old and while his father was serving in the Confederate Army young Theodoric stayed at home and helped look after his mother and sister as best he could. Living at the time as they did in a border state, they were subjected to frequent raids from the Yankees particularly from the soldiers of General Franz Siegel. On one occasion he

2

buried some family silver and other articles of value under a peach tree in an orchard near the house. He did not bury it very deep and the Yankee soldiers tethered their horses to these trees. The horses pawed at the ground and my grandfather stayed out in the orchard all night to see that they did not expose the valuables. One article was the gold watch mentioned in the biography of Dr. D. A. Linthicum. Other articles of silver we have and are still using.

When he was about fifteen years old he moved with his family to Helena. Nothing is known by the writer about his boyhood during this period except that he served his apprenticeship in the drug business for several years. In 1871-1872 he attended a course of lectures at the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy. Continuing this objective he was in 1873 graduated from the St. Louis Pharmaceutical College. After this he again matriculated at the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy from which he graduated in 1876. It was during this period as a student he succeeded in combining certain chemicals which had never before been accomplished. This moved the practice of pharmacy and medicine ahead to a marked degree.

In 1877 he married Louisa Bowman Stirling of Bayou Sara, Louisiana, the daughter of a prominent sugar planter of that state. Of that union there was one son, named for his grandfather, Daniel A. Linthicum who is in turn the father of the writer. At this time Dr. T. C. Linthicum was in the drug business.

In 1879 he attended the Ohio Medical College of Cincinnati, Ohio from which school he graduated in 1880. He then attended the Kentucky School of Medicine in Louisville, Kentucky and graduated from there in 1881. From that time he practiced medicine in Helena with great success and was one of the leading physicians of that section. He was a member of the Phillips County Medical Society and numerous Medical Organizations within the state of Arkansas. He served as President and later as Secretary of the Phillips County Society. For eight years he served on the United States Board of Pension Examiners under both Republican and Democratic Administrations.

In the 1890's his health began to fail and he took trips to Eureka Springs, Arkansas thinking the waters and the Ozarks in general would be of benefit to him. He stayed at times at the Crescent Hotel which was new at that time. He suffered with what in that time was known as rheumatism, probably arthritis today.

3

About 1902 he gave up the practice of medicine in Helena and moved with his family to West Texas. A new area was opening up in the Panhandle on what had formerly been the XIT ranch. He engaged with his son in the cattle business having homesteaded land in New Mexico until 1906. At that time a new town by the name of Farwell on the New Mexico-Texas state line had begun to boom and he returned to the drug business there for several years. About 1910 when it was discovered they could not make Chicago a suburb as had been hoped the bubble burst.

In 1912 he discovered a method whereby Hydratis Canadensis, the root of the goldenseal, could be combined with other ingredients to give it a pleasant taste and still take advantage of its known great curative properties. This product was marketed under the name of 'Lintholine.' He moved to Los Angeles with his son and family and established with his son, 'The Linthicum Chemical Company.' This project was later given up when it became evident that more money was required than was available to properly market this product.

In 1915 he returned to the ranch in Texas and there with his wife Louisa lived until 1929. He had long suffered with diabetes and in 1929 died as a result of this disease. For some reason he did not desire to have his remains returned to Helena and was buried in the cemetery in Farwell, Texas. His wife survived him by fourteen years. She remained in Texas until her demise in 1943. She is buried by his side in the Farwell Cemetery.

Thus ended a long life and career spent primarily in the relief of suffering, one of diligent and hard work in his chosen career. As has been oft repeated of him, 'for Dr. T. C. Linthicum just to walk in the sickroom, the patients felt better immediately.' Such was his kindly manner and great personality.

Captain Linthicum is a retired naval officer, who has also taught at Emory University in Atlanta. He and his wife moved to Branson, Missouri last year. There they have many lovely things in their home which belonged to his grandfather and great grandfather, the desk pictured in the last Quarterly, a chest used for storing medicine in the medical office, several other pieces of furniture, and china and silver.

4

The 1900 City Directory of Helena lists Dr. T. C. Linthicum as living at 602 McDonough Street, with his office at 511 Cherry Street. Most of the north to south streets of Helena had their numbers changed sometime between 1900 and 1909. Probably Cherry was one of them, and if this were the case, then his office would now fall in the 700 block.

Captain Linthicum's parents were buried at Helena as were his great grandparents. He is a cousin of Mrs. Sam W. Tappan.

MARTIAL SPIRIT ABLAZE

From Helena World, April 27, 1898

Helena Light Guards, Sixty Strong, Elect Charles P. Sanders Captain, W. B. Pillow First Lieutenant, and John E. Fritzon Second Lieutenant.

The meeting of the Helena Light Guards was largely attended last night, both by regular members and by volunteers. There were many visitors, too, including quite a number of ladies. In fact, all the seats were occupied and many stood up throughout the drill. Captain Hargraves drilled the company for an hour, while Second Lieutenant Pillow handled the awkward squad. At the close of the drill Capt. Hargraves asked all who wished to volunteer for service in the regiment now being formed to go to the Spanish war, to step three steps forward. For a moment there was a breathless silence, and a look of intense expectancy on the faces of the visitors as they leaned forward to scan the company. Only a moment elapsed, however, when almost the entire company stepped forward, quickly and boldly. There was another brief moment of silence and then the old hall was shaken by cheer after cheer of approval and commendation. In fact there were more war people present than had been suspected were in the whole city.

In justice to the few members who did not volunteer, it may be said they have very excellent reasons for not doing so. In fact it would be simply impossible for some of them to go.

The company was then given a little more practice and dismissed. We publish below a full list of the Volunteer Roll, which

5

will be sent to Governor Jones today:

| W. B. Pillow | John E. Fritzon | C. P. Sanders |

| Scott Crull | W. B. Newman | R. H. Fitzhugh |

| Will Crull | John M. Quarles | Jim Carter |

| Frank Moore | Cage Rembert | S. H. Fritzon |

| J. H. Geduldig | F. H. Merrifield | C. P. Stewart |

| Henry McCabe | S. P. Hanly | J. W. Carter |

| R. H. Johnson | M. A. Davis | John Powers |

| E. D. Briggs | Chas. C. Geduldig | Joe Giddens |

| Jos. Higgins | H. E. Smith | F. A. Daner |

| W. J. Leo | F. E. Chew | W. B. Bateman |

| Nicholas Rightor | Walter Southard | W. M. Douglas |

| John Prithoda | Jack Minton | W. J. Kilby |

| Louis Solomon | John Rainey | Geo. Sanford |

| Sidney H. Bailey | Chas. Gidt | J. R. Summers |

| C. W. Willis, | Goble | L. J. Wilkes, | Indian Bay |

| W. T. Cartwright, | Indian Bay | W. F. Nance, | Brinkley |

| R. B. Heathcott, | Postelle | J. R. Thompson, | Postelle |

| J. E. Mack, | Brinkley | C. P. Norman, | Brinkley |

| Ferd Billings, | Marianna | Fred Sutton, | Marianna |

| George Smith, | Marianna | Harry Nunally, | Marianna |

| Colney Bingham, | Marianna | Tom Wood, | Marianna |

| G. B. Thomasson, | Marianna |

Editor World:

There was a large gathering of the colored men of the city, at K. of P. Hall on 25th of April 1898, for the sole purpose of organizing a company of soldiers, to be tendered to the Governor of the state. This company's intention is to assist in whipping

6

the devil out of Spain, for the destruction of the Maine. There were patriotic speeches made to that vast crowd by our brilliant lawyer, C. C. Caldwell, who in glowing terms, told the people he was proud of the spirit that was manifested and the interest shown in "Old Glory." The meeting elected Mr. Caver as Chairman, and Prof. Emerson, secretary. Then Mr. H. W. Haliway stated the object of the meeting in a very able speech and then the chairman also made a neat speech and when he sat down, Mr. Caldwell suggested a patriotic song in which he led and while the singing was going on the men filed around the table and signed to the even number of sixty-six. Mr. H. W. Haliway was elected for their instructor for the present. Many more will join, at the next meeting which will be Monday night coming. The Spaniards will catch Hallilujah when these boys meet them.

"Inspector."

7

INDIAN MOUNDS IN PHILLIPS COUNTY

by

Louise M. Griffin

There were many Indian mounds at the foot of Crowley's Ridge along the Mississippi River. According to radiocarbon tests, they dated back approximately 2000 years. These mounds were here when De Soto landed on the banks of the Mississippi River in 1541 and the Indians considered them sacred, even if they or their people did not build them.

These mounds were full of pottery and other Indian artifacts. Later when white settlers came, the Indians were driven out and the mounds forgotten, until their rediscovery by accident while workmen were excavating dirt for levees or building terraces for houses and other practical purposes.

John Quarles knew in 1852 there were Indian burials on the estate he bought from Patterson five miles from Helena in that year. General Gideon Pillow discovered mounds at "Old Town" before 1878, while making a levee. He sent a valuable collection of pottery from these mounds to a museum in Nashville, Tennessee and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D. C. The relics from these mounds caused much interest and collectors and students of anthropology came into the country from numerous places over a period of years. Large quantities of the best specimens may be found in museums throughout the United States.

Judge M. L. Stephenson realized that soon the continuous excavation of these mounds would leave no Indian artifacts in Phillips County. He and his wife gave a valuable collection of old relics from these mounds to the library in Helena. This collection is housed in glass cases, and is cared for by the custodians of the Helena, Phillips County Library and Museum.

In 1940 Dr. James A. Ford, James B. Griffin and Phillip Phillips, archeologists of The American Museum of Natural History, New York, made an archeological survey of the Mississippi River alluvial valley and they came across the five prehistoric sites in Phillips County, Arkansas, on the eastern edge of Crowley's Ridge. The archeological surveyers were very much impressed. In their field notes were written these words: "A very spectacular site, mounds occupying a commanding position

8

at terminus of ridge with fine view of river and valley."

Because of the situation of these mounds at the edge of Crowley's Ridge and the loess soil (a fine powdered, yellowish silt of clay) that caps the ridge, after ages of time the ground had eroded into deep gullies leaving narrow rounded ridges that resembled mounds, and the mounds resembled part of the ridge.

In the spring of 1948, Dr. Ford had the opportunity to revisit the locality. He expressed disappointment and that it was a depressing experience to discover the mounds of the previous survey had suffered the same fate that had overtaken hundreds of other archeological sites, since heavy earth moving machinery came into common use.

One mound had been completely destroyed to provide space for a gas station and parking space. The bulldozer operator had found artifacts consisting of bones, pottery and shells. A few objects were given Mr. Johnny Greco and he placed these on display at his restaurant across the road, and one by one they disappeared.

A house had been built on another mound, which had been partly leveled. One had its southern edge trimmed by a new road, but fortunately not far enough to touch its central feature. On this same mound into the southern side a Negro citizen had dug a cave and was rearing a family there, until his abode was exposed by the construction of the new road. It was fortunate again that no damage was caused to the mound site. This mound was in danger of destruction as a bridge across the Mississippi was in the process of construction and the approach would run into the bluff in front of the mound site. To the east and west of the remaining mounds a large area had been leveled by borrowing earth for road construction. This area was soon to be occupied by a motel. Because of the destruction of these mounds for commercial use, Dr. Ford came back to excavate the mounds September 12, 1961, ten years sooner than was planned.

A crew of seven to ten men worked under his direction and that of Asa M. Mays, Jr., a graduate student of anthropology from Ohio State University. James Hulsey of Helena assisted in clearing tombs and other special work. The work was begun in an oppressive heat wave; the trowel work on the last four log roofed tombs was done in freezing rain inside a tent enlarged by poles and

9

sheets of plastic and was finished December 20th of the same year.

Besides the changeable Arkansas weather, the workmen were constantly interrupted by continuous groups of people, both children and adults. The crowds came out of curiosity, except for a few seeking information. All were treated with courtesy by supervisors and workmen alike, even though in Dr. Ford's anthropological papers is recorded, "artifacts removed by children from one of the mounds."

The burial complex of the Hopewell culture of Illinois is well known, and closely related Marksville culture is known in Louisiana from excavations; however, there existed a geographical gap in information, approximately 400 miles long through the central part of the valley. The Crowley's Ridge mounds located near the center of this gap made them of special interest for they promised the needed information about Hopewell burial practices.

Crowley's Ridge mounds were constructed by slave labor and women of the Indian tribes, that inhabited this country 2000 years ago. Basketful by basketful the earth was dumped in the manner brick masons lay brick. This was done over a given area and built to a designated height.

Dr. Ford explained that a shallow pit was made, sometimes small poles were laid on the earth and covered with skins of animals and the corpse was placed on this. The pit was lined with large logs and after the body was placed within, a log top covered the pit. Often other burials were made on top of the dirt fill of the first tomb. After alternate burials, the mounds reached a great height and temples were sometimes built upon them and a High Priest performed religious ceremonies, even human sacrifice. Only the High Priest and ruling classes were buried in these mounds.

A detailed account of the mound excavations and the artifacts found was written by Dr. Ford. These records were given to the Phillips County Library and may be borrowed or read on request from the library. Ask for "Hopewell Culture Burial Mounds Near Helena, Arkansas" by Dr. James Ford.

After 1961 all trace of the mounds built by the Indians 2000 years ago were gone with the exception of the decapped one with the house on top. After the anthropological crew finished their

10

excavation, bulldozers came, and the remnants of the mounds were leveled and the dirt hauled away. The removal of this dirt was quite a contrast to the building of the mounds when dirt was brought by man one basketful at a time.

Crowley's Ridge now stands sentinel, the only evidence of the written word and artifact displayed that there were ever any Indian mounds in Phillips County.

LIEUTENANT HORNOR PROMOTED

From Helena World, April 27, 1898

Lieutenant John S. Hornor, Third Lieutenant of Company G, First Regiment A. S. G. (Helena Light Guards) has been appointed lieutenant-colonel and chief of staff on the staff of Major-General V. Y. Cook, of the Arkansas State Guards. When the news of the appointment reached the city the many friends of Lieutenant Hornor besieged him with congratulations. The World begs to join with his friends in congratulating Lieutenant Hornor on his promotion and to say that Major-General Cook made no mistake.

John S. Hornor is an energetic and popular young man. He is a graduate of the Virginia Military Institute and well up in military tactics. He is a recent member of the Helena Light Guards and was elected as Third Lieutenant soon after he enlisted. He will give a good account of himself.

11

THE DIARY OF FRED B. SHELDON: PART II

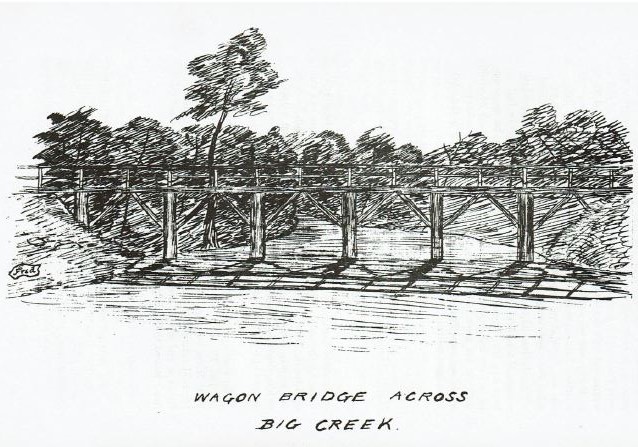

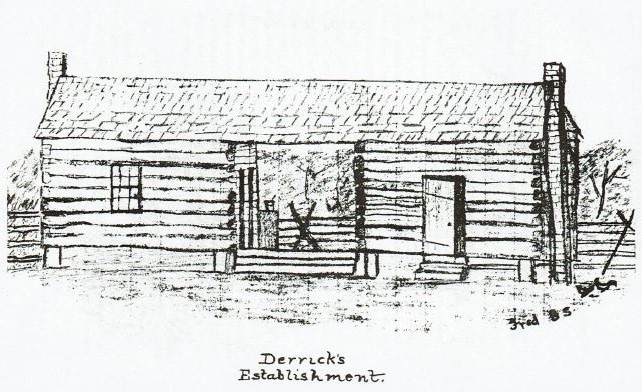

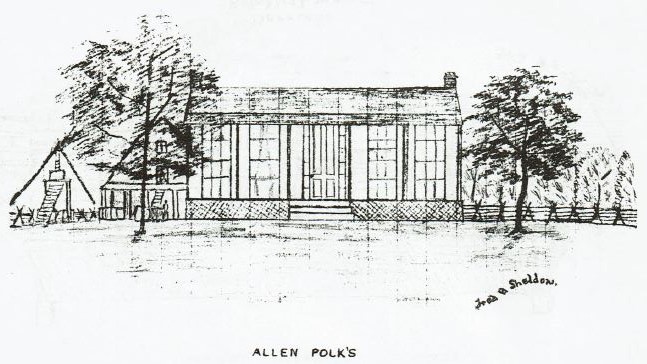

Fred Sheldon was a fourteen year old English boy who was in Helena in 1870, helping survey the route for the Arkansas Central Railway. He kept a diary during the course of the survey, and transcribed interesting events from his diary into this journal to be sent to his family in Kansas.

Tuesday, Nov. 29. Although it poured in the morning yet we went to work, being glad of any excuse to get away from Lunsfords. At noon we struck for the road, to find a house where we could dry our clothes and eat our "damp" dinner, and succeeded at last in finding Jones Store where we eat our dinner and got dry. Then we went back to work, and got up to Bridges at night.

Wednesday, Nov. 30. We laid up all morning to recruit our strength. After dinner we went to work and levelled half a mile, and then went back. In the evening we went up to Bunches, (a house about a quarter of a mile up the road) where the transit party was staying, and John Pinkerton who had charge of the party said he wanted me to take the back flag in his party, so after playing two or three games of chequers we went back to Bridges. Mr. Miller came out.

Thursday, Dec. 1. I got up early, said good bye to Tappan and Cass and went up to Bunches to breakfast. I found the transit party contained,

John Pinkerton — Transit-man.

John Hale — Hind Chain.

George Pinkerton — Front Flag.

John Costello — Stake maker.

Peter Galvin — Axe-man.

and myself — back-flag-man.

My duty was to carry a pail of dinner and attend to the backflag, also to carry coats or anything that there was to carry. We got as far as Big Cypress by night and walked back to Bunches. Bunches had the finest sweet potatoes I ever tasted.

Friday, Dec. 2. We left very early as we had a walk of 5 miles through cane brakes and swamps, but did not get to work till half past ten. We saw several deer. About 2 o'clock we sent out an exploring party in search of a house, but they returned in about half an hour unsuccessful, and we had a walk of seven miles back

12

to Bunches, where we arrived at six o'clock. Although it was December, the weather was just cool enough to work or sit still without perspiring or being at all cold. Cass came up and spent the evening with us.

Saturday, Dec. 3. We made about 2 miles and then set out, with a compass to guide us, in search of a house which we found out from the section we were in must be about two miles distant. Pete and Jack "blazed" the trees (that is they cut off the bark so as to leave a large white patch) all the way along, as we went on through the woods, so that we could find our way back in the morning. We found that we were coming to a clearing at last, and then saw a house. John Pinkerton rushed up to it but it was deserted, and John had lots of jokes told upon him afterwards about the "Pinkerton Hotel", as it was named.

Jack and George set off to a house at a little distance to enquire for Herod's house the one we were looking for. When they got nearly up to the door two immense dogs sprang out at them and they had to defend themselves with their axes, until some one in the house drove the dogs off and locked them up. They came back to us and took us to Herod's, having found out, at the "dog house", the place of abode of that worthy; and after a good deal of arguing he consented to keep us.

Sunday, Dec. 4. We passed the morning mostly indoors. Johnnie Hale and Jack went out for a short walk and saw some deer. In the afternoon John, Johnnie, and I went out for a walk and walked 15 miles. Having 3 Johns in the party we always called John Pinkerton, John, John Hale, Johnnie, and John Costello, Jack.

Monday, Dec. 5. Left Herods and in addition to our dinner bought as many sweet potatoes as we could carry. When we got about half a mile some of the men felt in their pockets and produced about two dozen eggs and put them in the dinner pail. Each of the party eat one at noon but me as I did not care for eggs unless cooked.

About 5 o'clock in the afternoon we left off work and just as I was getting over a fence into the road I found that while I was getting over I had let the pail fall and all the eggs were broken but two. Johnnie Hale and Jack came up and eat the two that were left, so they had their share of the eggs, yet no one ever

13

complained at the loss of the eggs except those two. I was glad I had not eaten any for I found out they were stolen at Herods. The men said they would not have touched them, if Herod had not charged us two dollars more than he ought to have done. We found a road leading north from the line, and after following it for about two miles we came to Mrs. Harvey's, and got permission to stay all night.

Tuesday, Dec. 6. We left our overcoats there and went out to work, as we intended going back there at night. After making 2 1/2 miles we started home, and found that we were only half a mile from the house.

Wednesday December 7. We again left our coats fully expecting to go back at night, but Mr. Miller came from town with letters for us, and then took our overcoats on with him to Clarendon, and at night, he sent a hack to take us into Clarendon, then about four miles from where we were at work, but the driver went off without us, instead of waiting as he had been told to do and we walked into town, and spent the night at the Hotel.

Thursday, 8th Dec. We went in a hack to where our line crossed the Clarendon Road, and then walked up the line and went to work. At noon we got to the bank of White River, and found the distance across, by triangulation, to be 678 feet. The distance from Helena was 43.8 miles the last stake east of the river being marked 2315, and as there are 52 stations and 80 feet on every mile, therefore 2315 divided by 52.8 gives number of miles.

We walked into town along the River bank, and stayed at the Hotel.

Friday, Dec. 9. We hired a man to drive us into Helena. He was one of those shiftless good for nothing kind of men, and was immediately named Sandyclos by our outfit. He had a good wagon and two poor mules. We drove all day and only got as far as Bunches by night. We put up there for the night.

14

Saturday Dec. 10. When we got up we found that it had been pouring all night and seemed likely to do so all day; however we were pressed for time and had to go on in the rain. I sat in the wagon and held the transit, and the others walked. At noon we pulled up and eat our dinner, and then the weather began to clear a little. Sandyclos could hardly sit up so I took the reins from him and drove along very well until we got to a store where we found Pete and George both rather full of whiskey. They helped old Sandyclos out to warm himself at the fire, and Pete gave him a drink of whiskey, but he no sooner swallowed it than he fell back in a fit. We got some water and brought him to, but he seemed to have lost his senses, he foamed about and although he could walk did not seem to know what he was doing; the storekeeper would not have him and we were compelled to put him in the shaking wagon again.

End of Part First

Part Second (not written up)

Death of Sandyclos. I remember occurred two days later in a house by the side of the Road, where we left him in care of a colored family, after trying every house for 10 miles in vain for some one to take him in, at the Company's expense. We sent a doctor to him, drove his team into Helena, where my diary shows we arrived at 6 P M the same day Saturday Dec. 10, 1870.

On Monday Dec 12 we started out on Location, reached Clarendon Jan. 10, 1871. Next surveyed several routes across the White River bottoms, and decided to cross at Aberdeen. On Feb 16, 1871 returned to Helena as detailed in letter to my Grandfather at end of this book, and became Draughtsman in Genl Office. Moved to Columbus, O. May 28, 1872.

15

16

17

18

HELENA AT CAMP DODGE

From Helena World, May 11, 1898

What The Helena Contingent Is Doing. Camp Dodge, Little Rock, Ark.

May 6th, 1898

Special correspondence of the World:—

The Helena Light Guards are at last domiciled at Camp Dodge, the temporary quarters of the Arkansas volunteers. Our trip from Helena was an eventful one, the people along the route showing their interest in the boys in many ways. At Marvell several cannons were fired, while young ladies and children pressed forward to the train and loaded the soldier boys down with flowers. The people of Holly Grove were also out in large numbers and loaded us down with flowers.

At Altheimer we were joined by the Jefferson Fencibles, of Pine Bluff, and journeyed with them to Little Rock, where we were royally received. The whistles of the mills, locomotives, factories, etc., were turned loose in our honor, as we marched through the streets to camp. Our first night in camp was one which the boys will never forget. There was carelessness, or something, in the Quartermaster's department, and we did not receive supplies until nearly 10 o'clock. There was also a shortage of tents, and we had to sleep five and six to the tent while to every five tents supplies were sent. Our first supper was a very light one, and to add to our discomfiture we had to do our own cooking. Our woe was increased by a heavy rain, which wet things up and somewhat dampened the ardor of some of our young warriors. Of course there was dissatisfaction the next day, so much of it that quite a number of the boys had almost decided to give up and go back home. Our kick reached the Governor, however, and Col. Chandler, who put their heads together, and there was soon a decided change for the better. More tents were provided, more and better food prepared, a cooking stove set up in camp, and a more cheerful aspect reigned. Mr. Billy Lanford has been installed as chief manager of the food preparing department and we are getting our rations cooked in good shape. Consequently the feeling among the boys is much better, and I believe they have all about concluded to stick it out. At present we are sleeping four in a tent.

Capt. Sanders, and he is making a splendid commander, by the

19

way, and Lts. Pillow and Fritzon are doing all they can for the good of their men. Here is about how we are equipped:—each man has his tin cup, tin plate, knife and fork, a spoon, a washpan, a tick filled with hay, and one blanket. When the call for meals is sounded we get our plates, etc. and march in line to the cook's tent, where our cups are filled with coffee, (without milk) and our plates with a potato, a piece of meat and some salt. We then sit around on the ground, or go back to our tents and "make the best" of what we have. More regularity becomes evident at camp every day, and soon we will be fairly settled. There has been considerable "slipping through the lines," the boys being anxious to go down into the city and tackle the restaurants for a square meal, and to get shaved, etc. But this will be changed up shortly. Already is heard the call for "The Corporal of the Guard," around camp, the boys being caught without the pass word. The boys consider cakes, bananas, oranges, etc., great delicacies, and their sweethearts will have their everlasting love if they will manage to convey a few tons to our section of Camp Dodge.

There are about 800 men here now. The examinations will commence Monday (today) when we will know how many of us will succeed in passing.

Col. Chandler appears to be making many friends, and the impression grows that he will make a most capable officer.

Mr. Branch Martin, of Little Rock, so pleasantly remembered by the boys who came in contact with him during their last encampment at Little Rock, was this morning appointed Brigade Quartermaster. This appointment gives general satisfaction.

Billy Hamilton has done some fine work for our company, and is a most valuable member thereof.

Wright Landry arrived today, from Clarksdale, Mississippi, and enlisted with us. Bruce Ramsey, one of the regular members of the Light Guards, joined us the first night, and is going along with his (line omitted) day appointed Quartermaster of the Company, and is considered the best man in the ranks for the place. The boys are in the best of spirits and all send love and regard to the folks at home. I am kept very busy, but will get another communication to you as soon as I can.

Nicholas Rightor

20

THE ST. FRANCIS RIVER: AN EARLY HOST

by

Dale P. Kirkman

THE FORT

Probably the first structure with any degree of permanency which was built by white men in our locality, was the fort on the St. Francis River. The fort was constructed in 1738 and 1739, when this area was a part of the colony of Louisiana, a possession of France.

The early history of the lower Mississippi Valley is largely a French history. In 1673, Louis Joliet and Father Marquette explored the Mississippi River with orders to try and find a route to the South Sea, and to assess the possibilities of conquest of the Mississippi lands by France. They were followed by the explorer, Sieur de la Salle, who claimed the Mississippi Valley for France in 1682. Nearly twenty years passed before France tried to establish any colonies on the river.

In these early years when France claimed the Mississippi, Pierre le Sueur, in the service of France, was sent to the uppermost reaches of the river to seek out mineral riches. In 1700, le Sueur and twenty-five men in a long boat with great difficulty went up the river. After passing the Arkansas River entrance, they found a small river higher up on the west side of the Mississippi, which they named St. Francis.

Soon trappers, hunters, merchants, and missionaries began to explore the Mississippi and its western tributaries in earnest. Weston A. Goodspeed, in The Province and the States, Vol. I, 1904, wrote: "Here also were the hunters who ascended the river two or three hundred leagues every year to kill the cattle (buffaloes) on St. Francis river and make their 'plat cotes,' by which they dried part of the flesh in the sun. They salted the rest; made bear's oil, obtained buffalo robes, and sent all down the river to market in New Orleans". At this time, buffaloes were first found some thirty leagues above the mouth of the Arkansas River. Goodspeed also told of Father Paul du Poisson, a missionary at Arkansas Post in 1726, who knew of a Frenchman who brought down to New Orleans 480 buffalo tongues taken the previous winter on the St. Francis River.

21

One big thing that stood in the way of French development of the Mississippi Valley was the Chickasaw Nation, age-old friend of the British and enemy of the French, occupying northern Mississippi and western Tennessee (present day). The Chickasaws made life miserable on the river for the French, by attacking every boat that they could catch. Their depredations at French posts and settlements in the present state of Mississippi were unbearable, and they constantly stirred up other Indian tribes against the French.

In 1736, Sieur de Bienville, Governor-General of Louisiana, made an unsuccessful attempt to crush the Chickasaws in Mississippi, at the same time that another disastrous French-Chickasaw clash occurred near Memphis. This unhappy campaign against the Chickasaws was followed by the campaign of 1739-1740, in which the fort on the St. Francis River figured.

Three nearly contemporary accounts give much of the obtainable information about this fort, and they are joined here without benefit of footnotes. They are the letters of Bienville himself, The History of Louisiana by A. S. Le Page du Pratz, published in Paris about 1758, and Memories Historique Sur La Louisiane, Vol. II, by Dumont de Montigay, published in Paris in 1753. Two later histories help fill the gaps left by these accounts, the Goodspeed book and Dr. John W. Monette's book, History of the Discovery and Settlement of the Valley of the Mississippi, Vol. I, 1846.

Once again, Governor Bienville decided to try and put down the Chickasaws, with the Cliffs of Prudhomme, near the present site of Memphis, serving as the point of departure into north Mississippi. He asked for help from France which was soon sent, including an order to Governor Beauharnois of the Colony of Canada to send help, too. A large detachment was sent from New Orleans to build a temporary fort and a group of cabins at the mouth of the St. Francis River, and to put the fort in a state of defense. This was planned to be a general depot for military supplies, and for the sick.

Letter from Bienville to Count de Maurepas, Minister of the Navy

May 12, 1739 New Orleans

...with this conviction I sent out last September Captain De Coustilhas with the same engineer, seven other officers, one hundred and twenty-five soldiers,

22

some workmen and some negroes in six boats loaded with provisions and with the tools necessary to establish a depot in the neighborhood of this landing and to build there wagons and boats for the transportation of provisions and munitions of war and of the artillery equipment. I gave orders to Mr. De Coustilhas to verify the report of the engineer about the distance between the places by sending Frenchmen and Indians to explore the country as far as he could without any risk. The first news that I received a little while after my return from Mobile informing us that the establishment had been placed at the entrance of the St. Francis River, two leagues below the landing of Sieur de Verges informed us at the same time that Mr. De Coustilhas had died there of sickness a few days after his arrival.

The first convoy of French troops arrived at New Orleans in May, 1739, and went directly upriver by barge and boat to the rendezvous at Fort St. Francis in company with other allied groups. The troops proceeding upriver included Marines, colonial troops, local inhabitants, Negroes, and some Indian allies. The army reached Fort St. Francis and spent part of the summer there, the military commander arriving on the St. Francis after leaving New Orleans in late June. When the convoy left the fort, a small detachment staying behind as guard, it proceeded on north to the Margot River ( Wolf River ), where it disembarked.

The army built palisades and Fort Assumption near Prudhomme Cliffs. Troops from Canada poured in — French, Iroquois, Algonquins, Hurons — composing the finest army ever seen in these parts. This formidable army of French allies, whose strength has been estimated at 3500 to 3700 troops, stayed here from August, 1739 to March, 1740.

Another preparation going forward during the time that Fort St. Francis was being constructed and then Fort Assumption, was the attempted transportation of horses and oxen to the expedition depot on the St. Francis River. Evidently the following letter was written after the campaign was over, when Bienville was explaining to Maurepas why the campaign against the Indians fell short of the desired success. Bienville was going upriver and passed Fort St. Francis.

23

Bienville to Maurepas May 6, 1740 New Orleans

I learned with satisfaction as I passed Fort St. Francis that the transportation of the provisions and goods that have been collected was almost finished, and I there gave my orders to drive overland the oxen that had been left there until that time, in order to spare the fodder in the neighborhood of the Margot River which was extremely scarce especially in such a late season.

He went on to say in this letter that when the animals from the fort started off through the low swampy grounds, things went from bad to worse. In a week's marching time, more than half of the animals were lost. The rest were so exhausted on arrival that they were of no use. Besides these animals, 250 horses and 100 cattle were supposed to have been brought from Natchitoches to Fort St. Francis at the end of September. But the animals perished by drowning or were lost otherwise, and never reached the fort.

In another letter of June 1, 1740, Bienville related more of the tragedy of the horses. Supplies started arriving at the St. Francis in the summer of 1739, with horses eagerly awaited from Natchitoches and the Illinois country. After the terrible march overland to Fort Assumption, only 84 oxen and 35 horses finally made it there in mid-December.

In a letter of May 4, 1740, to Maurepas, Commissary General Salmon gave his opinion of the mistakes of the campaign. He said that the animals that left the Illinois country and arrived at Fort St. Francis in July, 1739, were in good condition. The whole trouble lay in the fact that Bienville let them go all the way downriver to the fort and then brought them back twenty-five leagues to Fort Assumption in the month of December.

The French allies stalled all winter at Fort Assumption, conferring with the Chickasaws and getting nowhere. The march was never launched against the Chickasaw villages. The troops ran out of food, and had to eat what horses were left to them. There was much disease at the encampment, and many died during the winter months, leaving very few men fit for active duty. The campaign resembled a stalemate more than a defeat or a victory, and money, time, and lives were spent with little result. The Chicka-

24

saw problem was not solved until a later date.

When Bienville left Fort Assumption with the whole army in the spring of 1740, the fort was razed as it was no longer necessary. Fort St. Francis suffered the same fate and was destroyed as superfluous, by the army on its way south.

THE SETTLEMENTS

There are several travelogues or travel diaries of men who came down the Mississippi River at an early date. Some of these men were foreign visitors who were interested in seeing America, some of them were traveling for the purpose of making scientific observations, and some came in a military capacity. A slight knowledge of this locality can be gained from piecing together their accounts.

Le Page Du Pratz, in the aforementioned book telling of Fort St. Francis, told something of the surroundings, too. The lands around the confluence of the St. Francis and Mississippi Rivers, thirty leagues above the Arkansas River, were covered with buffalo, though hunters hunted them every winter at this place. In the neighborhood of the St. Francis, French and Canadians went "to make their salt provisions for the inhabitants of the capital (New Orleans), and of the neighboring plantations," and they hired the local Indians to help them. They made salting or powdering-tubs from trees, which were in abundance—tall oaks, black walnut, fruit trees, papaws, and others. These were very fertile lands. The author also spoke of the banks of the Mississippi as being lined with bears, and he said that they often crossed the river looking for food.

Jean-Bernard Bossu was a French naval officer who made three different visits to the French colony of Louisiana, each time traveling on the Mississippi River. In a letter from Fort de Chartres in the Illinois territory, in 1752, as published in his book called Travels In The Interior of North America 1751-1762, he told of leaving Arkansas territory and traveling to Fort de Chartres. In the 300 league journey up the Mississippi, his party did not see a village or a house.

25

They saw many herds of buffaloes at the river's edge, and also deer and bears. The author found this hunting along the river very pleasant, and he said that "game is so plentiful near the St. Francis River that, when we camped on its banks, we found it impossible to sleep because of the constant coming and going all night long of swans, cranes, geese, bustards, and ducks."

In a later notation, in 1757, Bossu wrote that his party was camped overnight on an island in the Mississippi River, and the soldiers with him facetiously declared him governor of the island. He shot and wounded a bear, and then ran toward camp so the bear would follow and be surrounded. The soldiers held a mock court martial of the bear, and decided to crush its head so its fur would not be spoiled. Bossu kept the black fur, and the soldiers rendered the fat into grease, getting 120 pots of it.

Captain Philip Pittman of the British Army was in America helping to survey British territory in West Florida following the Treaty of Paris. He was on the Mississippi in 1770, and noted in his book, The Present State of the European Settlements on the Mississippi, that there were no more settlements or posts near the river from the time that one left Arkansas Post until Cascasquias in the Illinois country was reached, at a latitude 37 degrees, 43 minutes north.

Not so many years after this, in 1791, John Pope was traveling on the river going south. He remarked in A Tour Through The Southern and Western Territories of the Spanish Dominions of the United States of North America, that there was a slight snow below present day Memphis on March 18th. Going on south, on the next day six Choctaw Indians came aboard and brought the travelers strings of jerked venison, and the Indians received in return salt and bacon. A Pennsylvanian and a boy in a pirogue hailed the boat. The pirogue was loaded with bear and buffalo meat killed on the St. Francis River. The author spoke of a twenty pound "kitten" being caught and made into broth.

Two of the most illuminating accounts were recorded in the same year. One was that of Fortesque Cuming, a cultured Englishman traveling in 1808, called Sketches Of A Tour To The Western Country, and the other was that of Christian Schultz, Jr., also in 1808, entitled Travels On An Inland Voyage, Vol. II. They both had much to say about the St. Francis River settlements.

26

Cuming saw swans on the river between Memphis (present day) and Helena (present day), and was overwhelmed by mosquitoes. He saw Judge Benjamin Foy's settlement across from Memphis on the Arkansas side, consisting of a store, a nice house, horses and cattle. Foy had been here since about 1794, and was very hospitable to travelers. There were five families nearby, and a store and a few families over on the Chickasaw side. The Spanish Fort Esperanza below Foy's was gone in 1808, but the American Fort Pickering was near Foy's.

Cuming passed the mouth of the St. Francis, but willows overlapped the entrance, partly hiding it. He landed at a "fine well opened farm" a mile below the mouth, where a comfortable, nice looking two story cabin with a piazza stood. This was the first settlement that he had seen since leaving Foy's and the Chickasaw Bluffs sixty-five miles back, and it was the property of one Phillips of North Carolina. Though the place was attractive to the traveler, he could get no refreshment there, especially milk, as the settlers had made cheese that morning.

He went on down the river for three and a half miles to William Bassett's pretty, cattle-stocked place on Big Prairie, but still no milk. He continued on for more than four miles to Anthony's place, where he was able to get milk, salad, and eggs, and spent the nigh there in Anthony's harbor which was relatively free of mosquitoes. When he had stopped at Bassett's on Big Prairie, he saw other boats moored there, and two of these also came down to Anthony's for the night. (A later edition of Cuming's book noted that the town of Helena was ten miles below the mouth of the St. Francis.)

In describing Big Prairie, Cuming said that it was "a natural savanna of about sixty acres." opening on the Mississippi River on the right bank, with good herbage for sheep. Behind Big Prairie was a small lake eight or nine miles in circumference, which was formed in warm weather by the river, and which flowed up a small bayou spreading water over the low prairie. This became a fine meadow when the river fell, and when not used as a meadow (when the water was up), it held all kinds of fish. It was also watered by a rivulet which came from the west hills three miles away, and the place would be perfect for rice growing.

Two more settlements joined Anthony's on the river, and there were five or six others behind Anthony's which were not on the

27

river. Altogether, there were about a dozen families in the twelve mile stretch between Phillips' place at the St. Francis to a new settlement three miles below Anthony's. (According to his calculations, the future site of Helena was Anthony's or directly below there.) He said that all these people were from Kentucky, except Bassett from Natchez and one family from Georgia. The soil was good and the climate healthy. There were nice looking cattle, but the settlers did not grow grain or cotton except for their own use. The reason for the lack of cotton cultivation was that they did not have the machinery to clean it, as they were not financially able to erect a cotton gin. Cuming traveled on seventy miles to Arkansas Post at the Arkansas River, and on the way noted that seventeen miles below Anthony's the overflowed lands started, where the river banks were low.

Christian Schultz was traveling with some kind of investigative flotilla, and looked on the same people in the St. Francis settlements that Cuming had seen. He left Council Island and traveled thirty-two miles to the mouth of the St. Francis. He estimated the entrance to the St. Francis to be 200 yards wide, and mentioned that the river could be navigated up its course for 200 miles, or almost to the Ste. Genevieve mines in present day Missouri. Two loaded boats were at the river's entrance.

Five miles below the St. Francis were a few improvements on a natural prairie. Settlers, he wrote, finding the land already naturally cleared, took it over with no title or claim. Most of the settlers had come since the Louisiana Purchase, hoping the government would protect them in this new country. Schultz thought they should have the right to their hardearned improvements, and he felt sorry for these "poor objects."

He took a skiff from his boat and landed at the settlement. The women gave him a sample of the cotton they were spinning, which he thought of poor quality. They told him that there was swampland three-quarters of a mile behind this place. He only stayed on shore for ten minutes, but it took him an hour to catch up with the boat. He saw some Indians in canoes, which he thought were probably Choctaws, and saw a catfish in one of the canoes which he thought weighed sixty or seventy pounds.

Reverend Mr. Learner Blackman was a Methodist circuit rider from Tennessee who was descending the Mississippi River in late

28

1812 and early 1813, as a chaplain of Tennessee troops in General Andrew Jackson's army. He kept a journal which was published in the Tennessee Historical Quarterly of September, 1953. After leaving Fort Pickering (Memphis) he noted that there were scattered settlements on the west side of the Mississippi River in Louisiana Territory. The boats of the troops landed several times on the present Arkansas shore going down.

On February 6, 1813, Mr. Blackman wrote: "Started about 5 oclock we have passed thro. difficult places, thro mercy we have been preserved. Land blow St. Francis River (identified by editor of Blackman journal as Helena, 298 miles below mouth of the Ohio) found a white man with small family living on the bank of the Mississippi with one acre of cleared land according to his own account he raised he said 60 bushels of corn-off of that acre-he has been there one year beats his corn into meal with a Pistol seems in his mod of living to be removed but a small grade above the Indians. He says there are an numbers of families living on St. Francis River and likewise below him about 2 miles."

Another very descriptive account of the same locality, containing observations made in 1819 by Thomas Nuttall, is Journal of Travels Into The Arkansas Territory With Observation On Aborigines 1818-1820. It should be remembered that in the ten or eleven years since Cuming and Schultz wrote their memories of this part of the Mississippi, the New Madrid earthquakes had come and gone. Mr. Blackman had mentioned the earthquakes, but not in regard to the St. Francis area. Nuttall departed the Fourth Bluff (Memphis) and Fort Pickering, noticing as he left the nearby Chickasaws who were drunk on watered whiskey. Nuttall was a biologist.

The editor of a later publication of this book said that there was no record of a permanent settlement in 1819 at the mouth of the St. Francis River, though there had been settlers around since 1800, when John Patterson was born near Helena.

Nuttall's group saw that the river was full of snags and bars close to the St. Francis. They tried to land at a house near the entrance of the St. Francis, but the water was too fast, so they landed a half mile below here. They had some difficulty in climbing up the steep bank, but after getting on top, they found two people there at a house. They observed that the first house at which they had tried to land looked abandoned, and Nuttall

29

thought he could understand why. Though the land was good and out of reach of water, the whole area to him was gloomy and somehow horrible. He walked into the woods, noting that the trees were not much different from those in the North, but were loaded with mistletoe. The people that they had run into on landing told him that there were hills a few miles below here on the Mississippi River, opposite Island 60.

Nuttall and his party spent the night about a mile above Big Prairie. He described the latter as being a settlement of two families and three or four log cabins, a place partly abandoned since the earthquakes of 1811-1812. The people there told him that the earthquake created a depression that now allowed the settlement to be flooded with water. At that time, the Mississippi River also carved off one-quarter of a mile of land in breadth with houses on it, leaving only the two houses still there.

A few miles below Big Prairie and a short distance below Island 60, Nuttall stopped at a store. He saw good and higher land, but thought the whole vicinity was desolate looking since the “hurricane." Rushes and cane grew all along the river banks and stepping out from these — a short distance down the river at Little Round Island — were some bad looking characters, who tried to get the boat to come into shore. Nuttall's party was well aware of the pirates that abounded on the Mississippi River and did not accept this invitation.

Timothy Flint in The History and Geography of the Mississippi Valley, Vol. I, published in 1832, spoke of the St. Francis settlements as being "isolated and detached." Perhaps Helena itself was not so detached, however. The Englishman, G. W. Featherstonhaugh, in Vol. II of Excursion Through The Slave States, published in 1844, said that he had heard of Helena before he had ever finished his travels through Tennessee. He described it as "a sink of crime and infamy," and said that it harbored Negro runners, counterfeiters, horse thieves, and murderers. The travelers had one thing in common; they were very frank in their appraisals of the sights that they had seen.

30

MORE RECOLLECTIONS OF CENTRAL CHURCH

by

Mary G. Sayle

Feeling the need for a church in the neighborhood, Reverend James A. Warfield with the cooperation of Mr. Williford, Colonel Keesee, Mr. Ed. Hicks, Colonel Jarman, Mr. Roland Cook, Mr. Ford, Mr. Nat Graves, Sr., Colonel Longley, Mr. Bogan Gist, Sr., Mr. Ligon, Judge Jones (who, as the story goes, held court in the woods, seated on a log), Mr. Tom Bonner and others, built Central Church in 1879, in a beautiful grove of trees near North Creek. This church became the center of the social as well as the religious life of the neighborhood. On "preaching day" once a month every pew would be filled, and every Sunday morning there was a large attendance at Sunday School

These were occasions for neighbors to enjoy getting together, the men in a little group seated under the spreading oaks, whittling and talking; the women in their group inside the church. It would be hard to evaluate the number of lives that old Central Church touched and brought to God.

In the early years of the church one of the men would lead the congregational singing, getting the pitch by means of a tuning fork. But in 1895, Mr. George Warfield brought home his bride, a musician, from Clarksville, Tennessee; so the church immediately bought a small reed organ, and with "Miss Mary" at the organ many happy hours were spent singing grand old hymns.

A "History" of Central Church would not be complete that did not mention faithful, humble old "Happy Day" the janitor — his cheery greeting, "Howdy Marse Boss, Howdy young Mistis",—who smilingly met every carriage to help the ladies out and to take charge of the horses. Happy Day, although poor in worldly goods, felt himself rich in the esteem and affection of his "white folks."

The much loved Central Church was torn down after the vandals had done their damage. Memberships were transferred to Barton and Lexa churches. Of those memberships transferred, Mrs. Beulah Warfield, now at Heritage Home, is the only one living.

31

BACK ON THE FARM

by

Carolyn R. Cunningham

In the late 1890's when Papa was a young boy, he lived on a farm at Vineyard. This was located about eighteen miles northwest of Helena. He tells us lots of stories, but one I found interesting was about the trips to Helena in the fall of the year to sell cotton and buy supplies.

Each fall they made five or six trips by wagon. They would bring two or three wagons each time with as many bales as they could load on, usually five or six. They came in a group, maybe ten or twelve wagons. Neighbors and relatives who came together often were Mr. Bill Sallis, Mr. W. H. McGrew, Papa's step-father, Lewis Martin, and his father, Mr. Eugene Martin.

Papa's uncle, Luther Robards, always had fine oxen, and therefore drove an ox team. He drove ten or twelve oxen hitched to a huge log wagon, and could carry about twenty bales of cotton to the load. Papa said it looked like a big house coming down the road, and when Papa was too little to go on the trips one of his big thrills was sitting on a fence post and watching Uncle Luth come into sight on his way to Helena. If it were a dry year he came along kicking up clouds of dust, but if the rains had set in, the backs of the oxen were bent and they were pulling hard over the roads which were little more than trails. As Uncle Luth drew near there was much waving and calling out, and if he decided to stop for a few minutes, there was much hollering and directing going on. Sometimes ten oxen would want to do ten different things. Papa said this could get so exciting it was no trouble at all to fall off your perch on the fence post, which was a little risky in the first place. Uncle Luth lived about two miles south of Papa's family. He never made the trip with the mule-wagons as the oxen were too slow and could not keep up.

Preparations for the trip began after a regular day's work. They began to load the wagons about dark, working with lanterns. Similar jobs were going on at each farm, and the deadline for departure was midnight. As each man finished he pulled away from the barn, through the lot and out onto the road. The meeting place was in front of Mr. McGrew's whose farm bordered on the Rehoboth Church grounds. There was stomping and blowing, puffing and pulling and

32

then they were off on the twenty-four hour journey. Papa said they would get up on the bales of cotton and fall asleep, with two or three always staying awake to watch the mules. If other young boys had been allowed to go they played along the way, and when they got way behind, would run to catch up. He said everyone always walked at least half the way. An occasional lantern broke the monotony of the darkness.

Over the narrow, rutted roads they went east — to Lexa, LaTour, across Shell Bridge, and just about daybreak joined a regular battalion of wagons on the edge of Camp Ground Cemetery. There was a huge well there which made it the stopping place. The animals were watered and cared for first, and then the fires began to glow as the men went about preparing breakfast. The usual breakfast consisted of thick slabs of ham, plenty of eggs, biscuits (prepared at home to save time), boiling coffee filled to the brim of granite cups, and molasses, sorghum, I'm sure, made there on the farm; but then that's another story. Leaving Camp Ground they proceeded south to the Little Rock Road and headed for Helena, coming into town at what is now Perry Extended.

About the middle of the morning they arrived at the cotton shed and began to unload. The owner of the cotton took his samples and started on his rounds to get the best price possible.

Papa said his stepfather almost always sent his Negro drivers on the wagon trip and he and Grandmama would get up early the morning after the wagons had gone and go to Lexa or Poplar Grove and catch the train to Helena. Grandmama would go about her shopping and Lewie (his step-father) would be at the sheds waiting for the wagons. Papa said the cotton buyers he remembers were Horn, Straub, and Wooten & Epes. Prices ranged from five to eight cents a pound.

After the cotton was sold the farmer bought his supplies to be loaded on to the now empty wagons for the return trip. This would include four or five barrels of flour, a 350 pound barrel of sugar, and whatever else was needed, besides Grandmama's shopping. She had left five young daughters at home so there were always material and trimming for new dresses. The Negroes also made purchases and the middle of the afternoon found the wagons loaded and headed west, and the ones who came on the train waiting at the station.

33

About midnight the wagons began to arrive at their own gates and turned off one by one. Everyone called goodbye, and tiredly finished up the last duties. The wagons were pulled into the shelter of the barns and not unloaded until the next day.

While in Helena Papa always went to the river to watch the boats come in and go out, load and unload. This was an entirely different world to a farm boy. One of the trips he remembers best was one made when he was a very little boy, and he always got laughed at about. He had been worrying his stepfather nearly to death to let him go on one of the trips. So finally Lewie said, "All right, Joe, be ready to leave at midnight tonight, I'm putting you in the care of Josh," a trusted Negro who worked for the family, "and I'm giving you this calfhide to sell. The money will be yours to do whatever you like." Well, a richer little boy had never lived, in Papa's opinion. He sat upon the wagon and between naps dreamed what he would buy with this fortune he was about to come into. He knew, as did everyone else, that a great portion of it would go for bananas, for he loved them better than anything. As soon as he could scramble down off the wagon and grab his calfhide, he lit out for Mr. Frank Horn, who was a great buyer of nearly everything, and had a store besides. He paid Papa seventy-five cents for the hide, and Papa began at once to make his purchases. These included bananas, apples, oranges, and candy. He crawled up on a flour barrel and proceeded to eat for as long as he could. I forgot to ask him which ran out first, the food or his appetite. At any rate, Lewie found him with his goodies atop the barrel — dirty, tired, but happy and above all, full. And thereafter Lewie always told about the time Joe ate up the calfhide. But Papa thought it was worth all the razzing he got.

He never got over his love of bananas either. When we were children — there were six of us — Papa thought the biggest treat he could give us was to come home from town bearing a whole stalk of bananas. We all marched out to the smokehouse and it was practically a ceremony to hang them up just right to ripen, if they were still a little too green. Hourly all six of us Robards children were trooping through checking that stalk of bananas. It never occurred to us to touch or certainly not to squeeze. I don't know what we thought Papa would do to us, but it was past even consideiing.

Papa grew up, started his family in the same house, and for some years joined his friends and relatives in the same type of "wagoncade"—but time marches on, and a trip of this kind has slipped into the world of reminiscence.

34

If you have questions or problems with this site, email the TCGS Coordinator, Ms. Carrie Davison, or the Webmaster, Ms. Debra Hosey.

Please do not ask for specific research on your family here. Use the

Research Help page instead.