Tri-County Genealogical Society

"because the trail is here"

Phillips - Lee - Monroe Counties in Eastern Arkansas

Volume 20

PHILLIPS COUNTY

HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Numbers 3 & 4

June, 1982

September, 1982

FALL ISSUE

Published by

The Phillips County Historical Society

Meetings are held in September, January, April and June, on the fourth Sunday of the month, at 3:00 P.M. at the Phillips County Museum.

The Phillips County Historical Society supples the QUARTERLY to its members. Membership is open to anyone interested in Phillips County history. Annual membership dues are $5.00 for a regular membership and $10.00 for a sustaining membership, Single copies of the QUARTERLY are $1.25. QUARTERLIES are mailed to members. Dues are payable to the Phillips County Historical Society, 623 Pecan Street, Helena, AR 72342.

Neither the editors nor the Phillips County Historical Society assumes any responsibility for statements made by contributors.

i

PHILLIPS COUNTY

HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Volume 20

Volume 20

June, 1982

September, 1982

Number 3

Number 4

FALL ISSUE

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The Hornor House

Mr. and Mrs. Charles M. Young and the HELENA WORLD,

by Porter C. Young

The Presbyterian Church Claim

by Betty M. Faust

Indian Bay: MARVELL MESSENGER

The Diary of a Soldier: Thomas J. Key

Trenton, Phillips County, Arkansas School Picture

Contributed by Betty M. Faust

Chapters in Phillips County History, Chapter IV,

by Major S. H. King

John Hanks Alexander of Arkansas

by Willard B. Gatewood

Steamer St. Nicholas Wrecked 63 years ago

by J. H. Curtis

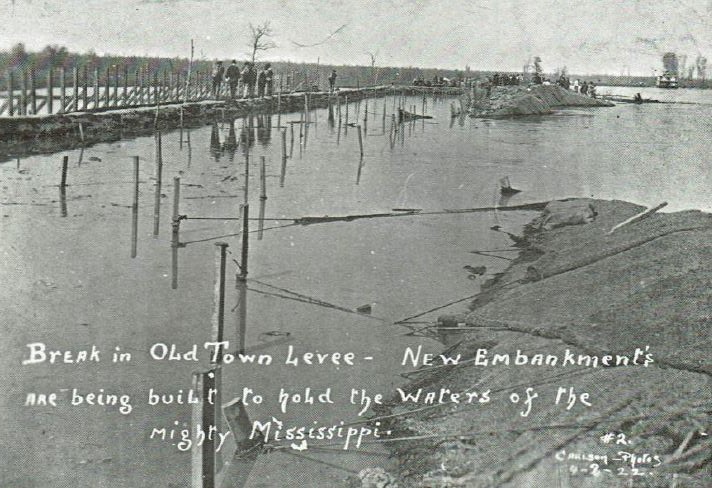

Old Town Scare-1922

by Thomas E. Tappan, Jr.

Notes

***

ii

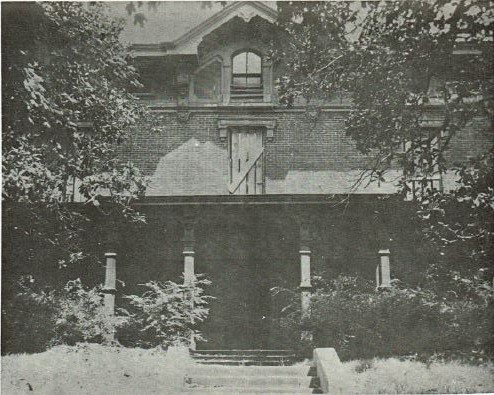

ON COVER: The home of Major J. J. Hornor and family as it looked when built, about 1867 It was located on the NE corner of Perry and Columbia Streets.

The picture on Page 1 shows the house after remodeling of the front, modernizing it to some extent. Time of this photograph was about 1910, and shows grandchildren sitting on the porch.

The picture on Page 2 shows the house in its last days, in the 1940s. It partially burned and was torn down,

iii

1

2

MR. AND MRS. CHARLES M. YOUNG

AND THE HELENA WORLD

by

Porter C. Young

This paper is from a speech given at the May, 1982 meeting of the Phillips County Historical Society.

My ancestors were early settlers in America settling in the territory of Carolina before working their way west. Grandfather David Allen Young was a farmer who settled on the banks of the Arkansas River in Jefferson County, near a town called Tamo, 12 miles south of Pine Bluff Floods were their biggest headache. When my father was eight years old, the family decided to move to Texas. Their small farm there was flood free, but they had trouble getting a clear-water well. Seems every place they drilled, they got greasy water. After three years the family returned to the old farm in Arkansas.

My mother, Estelle May Colhouer, was born May 3, 1888 in Pine Bluff, the daughter of Edgar Lee Colhouer and Demmaretta Lodley. She was educated at St. Agnes Academy in Pine Bluff. Her mother became bedridden with rheumatism and she was raised by an aunt, Mrs. Ida McCain, along with Mrs. McCain's 15 children. Her father was a carriage maker and undertaker by trade. He died when she was a child. Grandfather Colhouer was a veteran of the War Between the States.

Mother had a brother, Thomas Porter Colhouer, who was a columnist for the NEW YORK WORLD and was tubercular. She took her mother to the west

3

for her health, and divided her time between New York, Arizona and Pine Bluff. Dad described her as a “little snub nose, freckle face gal."

Dad came to Helena on July 31, 1910. In September he went west and married that little freckle faced girl. They were married in the Territory of Arizona by a bare~-footed monk in a church with a dirt floor on September 27, 1910. The marriage lasted 68 years, five months. They died just 28 hours apart in February, 1979.

Mother said that on the night they arrived in Helena as newlyweds (it was her first time in Helena) they came in on a train about 10 p.m. It was raining, and Cherry Street was a street of mud. In the first two blocks of Cherry Street were about 30 saloons. The sight of the saloons and the mud made her change her mind and want to leave Helena immediately. But she didn't. She settled down, helped out on the paper, took an active civic part in the community, and raised seven children--four girls and three boys.

My father was born on January 3, 1882. He was named Charles Madison Young. His mother's name was Burilla Isphene Pollack. He had several brothers, half brothers and a sister. Because of the distance from Tamo, his father engaged a man to come and live in their house and teach school to four of his children. To quote my father, "Well, that wasn't very good because we'd get up and go out whenever we wanted to." Some more people moved in the neighborhood who had children they wanted to send to school, too. My grandfather had a sharecropper that stayed on the place named George Allen, that was one-eyed, and always in trouble with the rest of the hands on the place. Grandfather moved George to a place on the very back side of the farm. He then took the tenant

4

house and opened a school there. My uncle promptly dubbed it "Allen College." Dad went to Allen College when he was six years old. The school lasted three years, or until the family moved to Texas.

The family moved back to Arkansas in 1893. In 1895 Dad, age 13, got a job on a weekly newspaper in Pine Bluff for the summer. He never quit working after that until his death at the age of 97. His job on the newspaper paid him $1 a week and he worked a ten-hour hay. His main job on the weekly was running the press. By running, I mean he was the horse power--or "kicker" as they called them in those days- The press was run by turning a large iron fly wheel. After getting it turning, a boy would kick it, keeping it spinning. The press had no electric motor.

His brother was working in Pine Bluff as a school teacher. He taught Dad reading, writing and arithmetic at night. Later Dad got a job on a daily paper in Pine Bluff, and went to business college at night. Later he took a job with the PINE BLUFF COMMERCIAL where he worked his way up from a collector to Business Manager, covering all jobs in between. He left there. in 1910 when he heard that a weekly paper was for sale in Helena. When he quit, he was making $35 a week, had managed to save $1,000 in cash.

Arriving in Helena, he paid $500 down on the weekly. That night several businessmen, J.C. Clamp, Ralph Lynch and others, sitting around the hotel, told him that the daily paper was for sale. He forfeited his money on the weekly and bought a half interest in the HELENA WORLD for $500 down. He took over operations on August 1, 1910. He bought the other half in 1912.

5

At that time the paper was a four-page paper. Today the paper averages 14 pages and revenues each day are more than he paid for the paper.

The HELENA WORLD was founded as a weekly in 1870 by William S. Burnett, great grandfather of Attorney Bill Dinning and Mrs. Ray Burch. He founded the daily on December 5, 1872. It is the second oldest daily newspaper in Arkansas today, and the oldest continuous business in Phillips County.

Mr. Burnett sold out to W. M. Neal. Mr. Neal moved the paper from its location on a side street between Ohio and Water street to Ohio street next to Feldman Commission Co., now the location of Edelweiss Antiques. The paper burned in February, 1919, and new equipment was purchased and the paper reopened at 311 Walnut street, where it was published for 42 years before moving to its present location on York street in 1961.

Mr. Neal, sensing he was not long for this world, gave the paper to his employees in 1902. He died just a week after completing the transaction. His widow later married E. S. Ready. I'm sure many of you remember Mrs. Ready.

My folks bought the paper from George Adams, Charles Underwood, Mr. Geduldig and others. Mr. Adams had an interest in a newspaper in Pine Bluff and left immediately to take over it's management. It was the GRAPHIC.

In 1908, the Editor of the WORLD, a Mr. Scott, was murdered by a politician. The crime took place in Newby's saloon, located near the corner of Ohio and York streets. J.P. Burks ran the WORLD for Mr. Adams from 1904 until 1908. His son, Edwin, was a paper carrier. Mr. Burks

6

moved to Pine Bluff in 1908 to manage Mr. Adams' paper and returned to Helena in 1913 to become editor for my father. Edwin worked on the paper as a carrier, in circulation and in advertising until he quit to open his insurance agency which he still runs today.

A man by the name of George Nicholls worked on the paper as a reporter for several years, later resigned and opened his own printing shop--Nicholls Printing Company. The WORLD's job printing department was sold about 1915 to Bradfield and Hydel. Alvin Solomon was working for the WORLD when Dad purchased it in 1910. Gene Foreman, now managing editor of the PHILADELPHIA INQUIRER, is a former employee. Mrs. Nanice Tappan Hornor is a former society editor. There are many others who started their careers at the HELENA WORLD.

In 1910 the WORLD was printed on a sheet-fed 2-page press. They later graduated to a 4-page press, then an 8-page roll fed press. In 1961 we changed over to a 16-page semi-cylindrical press and in 1971 installed a 24-page off-set press capable of printing four colors at the same time. In 1910 the circulation was 500. Today it is 7,500. In 1981 the WORLD was sold to Park Newspapers of Ithaca, N.Y.

Over the years there have been many newspapers come and go. Back in the olden days just about every job printer tried to put out a newspaper. As the industry became more sophisticated the job shops quit printing newspapers. Then, over the years politicians have attempted to start newspapers, but the American public has consistently refused to support such newspapers.

The HELENA WORLD did more than just print

7

the news. Back in 1932 Phillips County was in the heart of the depression and suffered a great drought. People were starving. Children were going to school on empty stomachs. The Red Cross allocated up to $4.50 a week to unemployed farm families for food. My father, as Publisher of the WORLD, sent a letter to every daily newspaper in the country asking for help. The results were astonishing. William Randolph Hearst sent his personal check for $1,000. One Michigan town sent six trucks loaded with food, accompanied by their mayor. Other loads were sent from the states of Washington and Colorado. State troopers accompanied the trucks to prevent highjacking. The food was stored in the basement of the Phillips County Courthouse and distributed to all the schools in Phillips County, parts of Lee and Monroe counties. It was the first hot lunches served by schools in Phillips County.

Early one Saturday morning shortly after that, a large crowd of blacks gathered outside Dad's home on Perry Street and asked to see him. He went to the door and was presented with a silver tray in appreciation for what he had done for Phillips County.

A sign on my desk for years said-- "I consider the day a total loss unless I catch hell about something." Such is the life of a newspaperman. He is damned if he does, and damned if he doesn't. People are funny. They want to see in print every little detail about their neighbor's shenanigans, but "don't you dare print the story about me."

I recall one old-time Helena lawyer, who had been hired to help prosecute a case in court, coming into the HELENA WORLD office and giving us a lecture on "never suppressing the news." He

8

wanted to be sure we covered the trial "in favor of his clients." But! The very next day he was in the office asking us to withhold the story on some of his kinfolks being arrested and jailed the night before.

Except for the most serious offenses, we never printed the names of teenagers who got into trouble. One day we had a story about two teenagers being arrested for stealing hubcaps. No names were printed. The next day I received a call from an anonymous lady saying "well, I read where two society boys are in trouble again, and you are protecting their families by not printing their names." The facts were: One of the boys was a 16-year-old being raised by his grandfather, a sharecropper. The other was a 17-year-old farm boy, a high school drop-out, home on leave from the army. But the story had a happy ending for me. The boys were found guilty in municipal court, given suspended sentences. They were sitting in the police station waiting for papers to be completed when I entered the room to copy the police blotter. They asked me not to print their names. I asked if they didn't know they were doing wrong in stealing hubcaps. "Yes, but this will kill grandpa if he hears about it," one boy said. I agreed to keep their names out of the paper, but told them that if I ever saw their names on the arrest blotter I would print the story about their previous arrest. A year later I was attending the high school graduation and the share-croppers grandson was in the class. As he walked down the aisle in his cap and gown, he spotted me, gave me a big wink and hand signal as if to say "I'm a good boy, now." I'll never forget it. Of course, I never had any intentions of printing their names in the first place.

9

We had a rule never to take wedding announcements over the telephone or accept them through the mail because too many mothers would announce their daughters engagement when the daughter hadn't even been proposed to.

But not everyone wanted to keep their names out of the paper. Some thrived on seeing their name in print. One late Helena lawyer had a philosophy to keep his name in the paper--good or bad news. "If you praise me, the people will think I’m great. If you print something derogatory, the people will think you're persecuting me."

Back during the depression days, things were tough all over. The banks closed. There was no money. I still have a note from the WORLD Publishing Co. for $12, money borrowed from my piggy bank to help make the payroll. When cash disappeared, the WORLD paid off each Saturday in scrip. For a while the merchants were spending those slips of paper just like real money.

At that time, a year's subscription by mail was $3.95. Most farmers didn't have the money, so they bartered.

Charles M. Young fed his family for several years on barter. Pigs, turkeys, chickens, hay and oats, sweet potatoes, etc. I've helped cut up many a whole hog that was swapped for a years subscription. The farmer wanted his HELENA WORLD and we needed the food. One lady at Turner exchanged pecans. When things began to improve financially, she still continued to pay her subscription with pecans, doing so until her death in the 1950s. We swapped ads to the barber for haircuts, with the shoe repair man for resoles, with the dry cleaner for dry cleaning. Tradeouts

10

were the way to stay in business.

Your daily newspaper covers history in the making, as it happens. The PHILLIPS COUNTY HISTORICAL QUARTERLY often carries stories taken from the papers of yore.

***

11

FIRST BUILDING 1849

Corner Ohio St. & Market St.

History of the First Presbyterian Church

Artwork - Ruth Green

12

THE PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH CLAIM

by

Betty M. Faust

The claim of the Presbyterian Church in Helena vs. the United States can best be traced in the voluminous claim papers accumulated in the years following the Civil War. This claim was for the use of the church during the occupation of Helena by the Federal Troops during the war and for the cost of repairing it after the troops left. The original claim was for the sum of $7,000. Only $1,900 in restitution was finally collected.

In 1849 the Presbyterian Church in Helena was founded with twelve members, ten of whom were women. A little more than a year later, in November, 1850, their first building on the northeast corner of Ohio and Market, facing south, was dedicated. During the Federal occupation the church was confiscated by the federal troops and used as a headquarters, a hospital and a workshop. The pews, pulpit and all available lumber were used and worked up into field desks. In 1868 when Rev. T.W. White took charge, the church was completely bare. A table which had been given to the church by Mrs. Anna Nash1 was returned to the church from the home of Dr. George McAlpine2 a ruling elder in the local church. The table had been kept there during the war. This same table is still in use in the Church Parlor in the Helena Presbyterian Church. The old communion service, which was buried for safekeeping during

13

the war, is on display at the Church.

According to the history of First Presbyterian Church, it was a woman, Miss Hattie White, who was responsible for placing a claim with the federal government for the damage done to the church building during the war. She came to Helena from Richmond, Virginia, with her brother, Rev. Thomas Ward White3 who served as pastor of the church from 1868 until 1872. Later Hattie White married James Graham.

The claim reads as follows: "Congressional Case No. 11706. U.S. Court of Claims, Old School Presbyterian Church, Helena, Ark. vs the United States. This is a claim for repairs, and for the use and occupation of the church building of the Old School Presbyterian Church, at Helena, Arkansas, by the military forces of the United States from July, 1862, to May 1865, stated at $7,000. The claim was referred to the court April 27, 1904, by resolution of the United States Senate under act of Congress approbed March 3, 1887, known as the Tucker Act."

The original depositions were taken in October 1891. The attorney for the church was P.M. Ashford. There were five witnesses as follows; Samuel I. Clark, Thompson M. Oldham, John J. Hornor, Angus W. Sutherland, and Mrs. Winnifred E. McAlpine. Mrs. McAlpine was the only witness who was a member of the church.

All of the witnesses testified that the church "as a church organization" gave no aid to the Confederacy. The rental value of the property was estimated from $25 to $100 per month. The attorney chose the lowest figure of $25 a month as rent on a carpenter shop. The building was occupied for 34 months, making $850 due for rent.

Witness ANGUS W. SUTHERLAND, age 47, was a contractor and dealer in building supplies, He

14

testified that "at the request of Mrs. Hattie E. Graham and other ladies of the Old School Presbyterian Church...I made a careful examination of the church building belonging to the said Church...and have made the following estimate of costs of putting said building in a suitable condition for ordinary church purposes..." His itemized list totals $1803.10.

Another witness, JOHN J. HORNOR, stated that he was not in Helena during the occupation but that he was familiar with the condition of the church at the beginning of the warm and also at the end. He rebuilt at his own expense the pulpit for $140, He remembered that the glass in the windows was almost all broken, the plaster was off and the "church was in about the condition one would expect to find after, occupation by soldiers for three years."

Witness SAMUEL I. CLARK, age 57, was listed as the Clerk of the U.S. Circuit Court. He was an officer in the Federal Army, serving first with the 1st Missouri Infantry, and then serving as 1st Lieutenant and adjutant with the 56th Colored Infantry when it was stationed at Helena from 1863-1865. Part of his regiment was quartered in the Presbyterian Church.

Witness, THOMPSON M. OLDHAM, a carpenter, had lived in Helena since 1853. He worked in the church as a carpenter during the occupation, making field desks for the Federal officers. He stated that "the seats and every movable thing about it was used up and the house itself was greatly damaged."

Another witness, MRS. W.E. MCALPINE, age 52, lived in Helena during the occupation and was a member of the Presbyterian Church. She described the damage to the building and concluded "that it was thought to be a hopeless task to attempt to repair the church."

15

From the Congressional Record, there are copies of Bills introduced in December 1891; January 1892; August 1893; December 1895; January 1896; December 1901; November 1903; January and April 1904. All of these bills are for "the relief of the Old School Presbyterian Church, Helena, Ark."

In 1895 the church building was destroyed by fire. Mr. J.W. Clopton4 recorded the fire in his diary as follows: "The small residence immediately back of the Presbyterian Church took fire about 3 o'clock in the morning and set fire to the church. Both buildings burned down. The old Church steeple with the old weather cock representing a harp, which had dodged the breezes 45 years, toppled over and sank in the flames. The church building was insured for $1900 and the organ for $200," The fact that the church had the building and contents insured for only $1200 which they collected after the fire greatly weakened their claim for $7000 from the United States. Plans began for building a new church. The old lot on Ohio was sold and the lot on the southeast corner of Porter and Franklin was bought for a new church5 the first service was held in the church in April, 1896-- just a year after the old building was destroyed by fire.

In the claim papers there is a Petition, dated April 27, 1904, to the Claims Court for the sum of $7,000, It is signed by the Trustees of the Church, S. A. Wooten6 and S. C. Moore, and their attorney, G. W. Z. Black.

Depositions were again taken at Helena on May 24, 1905, by E. R, Crum, Clerk of the U.S. Circuit Court. 7 Present were S. A. Wooten, representing the church, and Robert Chisholm, representing the United States. Depositions were taken from three witnesses that had testified in 1891 in the hearing for the original claim. These were Samuel I. Clark, Thompson M. Oldham, and Mrs.

16

W.E. McAlpine. Two of the original witnesses-John J. Hornor and Angus W. Sutherland- were dead. No new witnesses testified.

It was found from the evidence that the Helena Presbyterian Church, as a church, was "loyal to the Government of the United States during the late war of the rebellion." Also, "the military forces of the United States, for a period of eighteen months,...used, occupied and damaged the church building... Such use and occupation... was reasonably worth the sum of $1900, for which no payment appears to have been made," According to papers of the local Presbyterian Church, the sum of $1900 was received from the United States by the church.

Most of the information for this article came from the papers of the claim itself. Also used were previous articles in the QUARTERLY by Dale Kirkman about the claims of the First Baptist Church in Helena8 and the heirs of Dr. Deputy9 Histories of the Presbyterian Church that were used are in the 1904 Souyenir Section of the HELENA WORLD10 the church's scrapbook, and a church history in the QUARTERLY by John King, Jr. 11 My impetus for this article was an old yellowed newspaper clipping brought to me last May by Tucker McCollough Daggett which told of an appropriation bill introduced by her grandfather, Phillip D. McCollough, Jr., Congressman from this District. This was for the sum of $4500 for "the relief of the Old School Presbyterian Church of Helena." The Session Minutes of the local church were not available for research.

17

FOOTNOTES

1Mrs. Anna Nash was the great, great grandmother of Bart Lindsey, who is presently serving as Clerk of the Session at the Helena Presbyterian Church.

2Dr. George McAlpine was born at Port Gibson, Miss., in 1827. He graduated from the University of Maryland in 1850, married Miss Winifred Wigginton of Louisville, Kentucky, and moved to Helena in 1856. He was elected an elder in the Presbyterian Church in 1860 and served until his death in 1888.

3Rev. White and his sister Hattie White Graham were the great uncle and aunt of Graham White Woodin, an active member of the Helena Presbyterian Church.

4J.W. Clopton was the grandfather of Helen Clopton Polk Mosby.

5This is the present site of M-C Drug.

6S.A. Wooten was the grandfather of Wooten and Thea Epes and others.

7E.R. Crum took many depositions of witnesses in claims cases. A little record book that he kept in the 1890s of these depositions is in the Phillips County Museum.

8PHILLIPS COUNTY HISTORIGAL QUARTERLY, Vol. 17, No. 4, Sept. 1979, p. 30.

9PHILLIPS COUNTY HISTORICAL QUARTERLY, Vol. 18, Nos. 3/4, June/Sept., 1980, p.70.

10PHILLIPS COUNTY HISTORICAL QUARTERLY, Vol. 13, No. 1, Dec., 1974, p. 35.

11PHILLIPS COUNTY HISTORICAL QUARTERLY, Vol.3, No. 1, Sept. 1964, p. 15.

18

INDIAN BAY

From the MARVELL MESSENGER

Friday, July 15, 1966

Paper's editor: The following article, “Indian Bay," was written by the late Watt McKinney whose father was one of the first to build a clubhouse on the Bay. Clubhouses at that time were quite different from those being built now with all the comforts of "City Dwellers."

Indian Bay is the beautiful name of a superbly beautiful stream, a tributary of the White River, in a southern part of Monroe County. The two very words, composing its name, are suggestive of beauty, of romance, of tranquility, and of a home of an ancient race.

Indian Bay was so called by the early settlers of that area no doubt on account of the two large Indian mounds located there, one of which is unusually high and stands directly on the edge of the bay. From time to time over the past years, due to the action of a swift current in periods of high water, portions of this mound have caved away and fallen into the stream, revealing it as having been used in centuries past as a burying place for the dead, perhaps of those who built it. The other of the two mounds, located several hundred yards inland is now the neglected and abandoned site of a burial ground used by many of the early settlers of the community.

Adjacent to the shores of this beautiful stream, lies the site of the original town of Indian Bay, once a very thriving and prosperous

19

village, peopled by many wealthy, cultured and aristocratic families prominent in the affairs of the county and state. Extending northward and eastward for many miles lay broad, alluvial plantations on which were produced each year many thousands of bales of long staple cotton that contributed largely to the prosperity of the town and surrounding county.

According to records filed in the recorders office at Clarendon, the county seat of Monroe County, what was known as the Town of Indian Bay was incorporated and platted under the name of Warsaw, though it was never known by this name. It is situated in a Private Survey No. 2345, usually referred to as a Spanish Grant and located in the Southeast corner of Township Three South, Range One West. This survey comprised an area of two hundred and twenty-four acres and John Diana was its original owner as shown by existing records.

The first survey and map of the township in which Indian Bay is included was made by Deputy Surveyor, N. Rightor in the year 1825. With reference to this survey, it is interesting to mention that among a large collection of relics owned by one of the citizens of St. Charles, a village on the White River only a few miles distant, there is a slab of wood that was cut only a few years ago from the body of a huge cypress tree and on which appears the inscriptions made by this surveying party more that One Hundred years ago. This tree and its inscriptions, standing near a point cornered by four sections of heavily timbered forest land not far from Indian Bay was located purely by chance. A surveyor in the employ of a large timber concern was engaged in determining the boundaries of certain sections

20

and was using the filed notes prepared by Rightor as his guide in this work. Through his calculations, the surveyor was positive that he had arrived near the location on which stood the tree mentioned in the notes. There were many giant cypress trees standing about him any one of which might have been the one he sought and that bore the markings of a hundred years past. He had little hopes of locating the tree, when an axman swung his sharp blade and with the first stroke a large slab fell from the side of one of these age old trees, revealing the inscription concealed through a century's growth.

The first settlers or pioneers who are definitely known to have located in this part of Arkansas and Monroe County are the Mose Prices, J. Diana, Joseph Mitchell, A. Berdu, and Major Dukes, all of whom received liberal grants of land and established homes for themselves on or near the stream of Indian Bay.

The Town of Indian Bay and that part of Monroe County known as The Indian Bay Community were favored with an era of wonderful prosperity and growth dating from the period marking the close of the civil war up until 1890. Many large and substantial mercantile establishments were located there to supply the needs of its large plantation area. The most prominent of these merchants were M.D. Martin and Samuel L. Black who conducted a partnership business known as Martin and Black. In addition to their mercantile establishment, Martin and Black also owned and operated a cotton gin and saw mill. Among the other and prominent business concerns at Indian Bay were, Burge and Robinson, Silverman Brothers, Blaine and Hargis, B.F. and G.F. Johnson. Dr. Shipman was the leading physician and

21

Clem Clark was the proprietor of the Rainbow Saloon.

Major Samuel L. Black, father of the late John S. Black of Holly Grove several times Sheriff, County Judge and Treasurer of Monroe County, was one of Indian Bay's and the county's first citizens, a successful merchant, owner of extensive and valuable plantation properties and long prominent in the social, religious and business life of Eastern Arkansas. He was born in Fayette County, Tennessee, on March 22nd, 1842, coming to Arkansas when he was sixteen years of age. At the beginning of hostilities occasioned by the war between the North and South, Samuel L. Black enlisted in a company organized in Clarendon by Captain J.T. Harris for service in the cause of the Southern Confederacy. This, the first company organized in Monroe County, became a part of the first Arkansas regiment, commanded by Patrick R. Cleburne of Helena and Black was subsequently commissioned a Junior Lieutenant. He was promoted to the rank of Captain at Bowling Green Kentucky. The first major battle in which Samuel L. Black was engaged was that of the famous battle of Shiloh, where in recognition of his exceptional bravery and leadership he was advanced to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel and attached to Hardee's staff. He participated in Bragg's invasion of Kentucky and was at the surrender of the Federal forces at Mundfordsville and engaged in the battle of Perryville. Immediately after the battle of Murfreesboro in which he took a leading part and that resulted in such a decisive victory for the Confederate forces, Black was promoted to the rank of Major. He was in the battles of Chickamauga and Missionary Ridge, fought with the Army of Tennessee from Dalton to

22

Atlanta, was in front of Sherman in his march from Savannah through the Carolinas and was captured by a squad of Sherman's cavalry, but after being held a few hours escaped by a wild ride. He surrendered with the Confederate forces at Greensboro, North Carolina.

Among the prominent planters of the Indian Bay Community in that period marking the crest of its growth and development were Captain William M. Mayo, Sam R. Pointer, W.D. Burge, F.J. Robinson, Lawrence Mayo, M.D. Martin, B.P, Jackson and William H. Boyce.

Captain William M. Mayo, the owner of the most extensive plantation properties in southern Monroe County, moved there in the year of 1853 from Martin County, North Carolina, bringing with him a large number of slaves. Several thousand acres of undeveloped land were acquired by Captain Mayo, a large portion of which was soon placed in a state of cultivation. This estate, still the property of the Mayo family now owned by the grandchildren of its founder is considered one of the most valuable and productive properties in this section of Arkansas. Of the lands originally acquired by Captain William M. Mayo and still a part of the estate, there are several hundred acres of virgin forest, said to be the only remaining large and heavily timbered tract of land in this state.

Indian Bay was a regular port of call for steamboats operating out of Memphis and engaged in the White River trade. All merchandise shipments to the Memphis market of the vast numbers of bales of cotton and sacks of seed produced in the community. Among the boats that visited Indian Bay each week, it is recalled that the most noted of these were, the Hard Cash, Chickasaw, and Josie Harry. Captain E.G. Postal was

23

owner and master of the Chickasaw and Green Snow was one of the pilots. At the foremost part of the bow of the Chickasaw there stood a life-size figure of an Indian, a token to that race of people for whom the boat was named. Captain Milt Harry was owner and master of the Josie Harry that was named for his wife. Both the Josie Harry and the Chickasaw carried excellent appointments for the comfort and convenience of passengers. The Chickasaw sank with a heavy cargo one night as the boat was in the White River only a short distance above its junction with the Mississippi. The Josie Harry burned to the water's edge when in sight of the landing at Memphis, resulting in the entire loss of her cargo containing 1600 bales of cotton and more than 500 sacks of seed consigned by Indian Bay planters to Memphis merchants.

Extending from the shores of Indian Bay and its bayou tributaries there were in years a long past, broad areas of forest, heavy with the growth of giant cypress trees. These lands were the property of the Federal Government, however, it is said that many millions of feet of excellent logs were illegally taken each year, and that many men were engaged entirely in this business. The procedure followed by these in this unlawful practice was this, during the usual Spring rise of these streams, and the consequent overflow of their banks, these great forest lands were covered with water to a depth of several feet, and it was during these periods that the trees were cut, sawed into logs and floated out into the open water where the logs were tied together, forming a huge raft that was floated with the current down the river and sold to some large saw-mill at Greenville or Vicksburg. It is said that often several thousand dollars would be obtained for a single large raft of

24

cypress logs. Usually a cypress log will float, yet many of them will not, consequently many thousands of logs became detached from these rafts and sank, and it is said that Indian Bay contains many millions of feet of these sunken logs that are yet in a perfect state of preservation.

The stream of Indian Bay is formed by the confluence of several large bayous and its length from source to its junction with the White River is perhaps ten miles. Stately cypresses line its banks and here and there along its course beautiful bars of white sand extend out towards the stream.

The site of the former village of Indian Bay is situated about midway between the stream's point of origin and its mouth. The decline of the town of Indian Bay occurred some time prior to the year 1890 after which the declension was more rapid and continued until the place was practically abandonded. The decline of this once prosperous and growing community was caused by a number of successive floods of long duration and increasing destructions. Prior to the year 1882 the community had never been seriously affected by flood waters, but after that time beginning with the completion of a levee along the east side of the Mississippi River these disastrous and unfortunate occurrences visited the territory with increasing frequency finally leading to its inevitable financial ruin.

Indian Bay with its broad, deep bayous and wide expanse of forest adjoining its shores and embracing many, quiet, beautiful lakes has long been a favorite retreat of the sportsman. The waters abound in many varieties of fish in both the game and commercial species the dense forests

25

afford a place of sanctuary for vast numbers of wild creatures, huge flights of waterfowl annually visit this region and visitors each year in increasing numbers are finding enchantment in its wild beauty and enjoyment in the recreational facilities afforded.

Indian Bay may be reached at any season of the year over State Highway No. 17.

***

26

THE DIARY OF A SOLDIER: PART 2

Captain Thomas J. Key was born in Bolivar, Tennessee, on January 17, 1831, the son of Chesley Daniel Key who had emigrated from Virginia where he had been reared on a plantation adjoining that of Thomas Jefferson. In his early childhood young Key's parents moved to Mississippi, settling at Jacinto, the county seat of Tishomingo County. Here his boyhood was spent. When he was fifteen years of age, Thomas found employment in the office of the publisher of a weekly paper at Tuscumbia, Alabama, remaining in that position for four years until he had saved sufficient money to enter LaGrange College, in the same state. He was in attendance from 1850 to 1852, leaving school in the latter year to buy the DAY BOOK (more commonly referred to as the FRANKLIN COUNTY DEMOCRAT), the newspaper upon which he had formerly worked at Tuscumbia.

At this time the nation was greatly agitated over the question of slavery in the Kansas Territory, and the strenuous efforts towards colonization were being put forth by the slave and free states. At the height of the controversy, Key--with one hundred and thirty persons from Alabama--removed to the Kansas Territory where he himself began the publication at Doniphan of the KANSAS CONSTITUTIONALIST, the first issue appearing on May 4, 1856. Militantly slave and Democratic in its editorial policy, the paper was received with great hostility by the predominately Northern population that had settled in this part of the territory. Meanwhile, he was elected to serve in the celebrated Lecompton Constitutional Convention.

27

Key soon found that the Southern element in Kansas was fighting a losing battle because of the tremendous wave of immigration that was sweeping in from the North and East. Both he and his press were more than once thrown into the river, and when the Lecompton Constitution was rejected he decided to return to the South. Settling at Helena, Arkansas, on the Mississippi River below and opposite Memphis, he published a Democratic newspaper and served in the State Legislature. He was a member of that body in 1860 and voted for secession,

The main facts of Captain Key's military career are soon told. Having determined to enter the army, he enlisted as a private in Company G, 15th (Josey's) Regiment, Arkansas Infantry, on May 1, 1862, at Corinth. Almost immediately, however, he was transferred to Calvert's battery (Arkansas Light Artillery) of Hotchkiss's battalion, and in June he was promoted to the position of 2nd lieutenant. In this capacity, and later as 1st lieutenant, he took part in most of the fighting in northern Mississippi; in Bragg's Kentucky campaign; and, on December 31, 1862, in the bloody arid indecisive Battle of Murfreesboro, fought as the army retreated south through Middle Tennessee. Here he commanded the artillery which henceforth won fame as "Key's battery."

At the battle of Chickamauga, September 19th and 20th, 1863, he served with unusual distinction. In their official reports, Lieutenant General D.H. Hill, Major General Pat Cleburne, Brigadier General Lucius E. Polk, and Colonel B,J. Hill cited him for gallantry and effectiveness, saying that in the fiercest part of the struggle he ran his battery by hand to within sixty yards of the enemy's lines. 1 At the Battle of Missionary Ridge, fought on November 25, 1863, General Cleburne stationed

28

Key with his battery over the tunnel where the East Tennessee and Georgia Railroad passed through the ridge, and placed him in charge of all the Confederate artillery there.

In reporting that the batteries of Key and Swett bore the brunt of the fighting, he said that the former depressed his guns to the utmost and fired shell and canister down the hill in the face of a withering fire from the enemy. When the guns could no longer be gotten into position to command the precipitous slope, he led his men in rolling down stones upon the determined foe.2

With the retreat of the Southern forces after Missionary Ridge, Key helped form the rear guard which received the thanks of the Confederate Congress for saving Bragg's army from destruction, serving with particular distinction at Ringgold Gap on November 27th, Thereafter, the army went into winter quarters at Dalton while Cleburne's division, including Key's battery, acted as an outpost ten miles to the north at Tunnel Hill, Georgia (not to be confused with the tunnel through the ridge at Chattanooga). At this point the diary begins.

**

The entire diary is not printed herein. Selected parts that pertain to Helena, or people from Helena, are used, along with entries that are especially interesting.

IN WINTER QUARTERS

NEAR DALTON

February 5, 1864

Bade my friends adieu for a brief period and took the cars for Dalton where I gathered the

29

letters for friends across the Mississippi. The cars were so thronged with soldiers that I could not obtain a seat, and was therefore compelled to stand in the aisles almost the whole night. Shortly before daylight the train arrived at Atlanta.

February 6, 1864

Before sunrise I visited the railroad depot in Atlanta to get a ticket, and there I met Captains Kearns and Sherer, the former being "boozy," or in a jolly mood. He drew out a bottle and insisted that I shold drink with him. I told him that I did not make a habit of drinking, but he would not excuse me. We took seats together in the cars for Montgomery, Alabama, where we arrived that night, but nothing particular occurred save being most distressingly bored by a pretended doctor who made a hole in our commissary and devoured a liberal share of our medical supplies- whiskey.

February 7, 1864

Early in the morning we arose, deposited our baggage with the bar kepper, and bent our steps for a restaurant to get some genuine coffee, oysters, fish, etc. The Captain took on an overload of "medical supplies," and insisted (after Captain Sherer and I had eaten very heartily) that we should have more coffee and fish. He made a servant fill our cups and so we began breakfast afresh. The meal for the three cost $30. At 5 o'clock we took passage on a steamer for Selma, Alabama, arriving there about 5 o'clock P.M.

February 8, 1864

In order to see the city of Selma the two captains and I walked from the hotel to the railroad

30

depot. It is a beautiful town, with broad streets, the one which we walked up having a number of artesian wells on it. The residences are of a Gothic style, with front yards laid out in hearts, diamonds, and other shapes, and evergreens looking as fresh as a sweet sixteen Miss. The cars passed through a rich farming country until we reached Demopolis, Alabama, where we took passage on a small steamer down the Tombigbee River to the railroad four miles from Demopolis. At this place we heard that the Federal General, Sherman, had reached Jackson, Mississippi, and that the Confederate authorities would not allow us to go any further, but to our joy the latter part of the story was unfounded. Sunset found us at Meridian.3

February 9, 1864

At 4 o'clock A.M. I was aroused to take the cars for West Point on the Mobile & Ohio Railroad, the arrival of the Yankees at Jackson causing me to make a circuitous route, going north and then traveling west. Although I regretted to part from my agreeable captains, I fell in, before the day was gone, with a Mr. R. C. Davis of McNeil's Virginia Partisan Rangers. He had practiced law in Arkadelphia, Arkansas, was well read, polished in manners, and a true specimen of Southern gentleman. Arriving at West Point, Mississippi, we left the cars and I at once visited almost half of the houses in town in an effort to get a conveyance to carry us to Grenada. I had about despaired when I was directed to a Mr. Brame, whom I found to have an honest face and who talked to suit my feelings. Finally, he told me that if I could hire no one to take me across the country I should come to his house, a mile and a half in the country, and he would see what he could do for us. We called for dinner at a hotel, where we had pork and beans, but the females were beating eggs

31

and I discovered some cakes which, however, did not reach the table. As we walked into the bar-room I saw three shy lasses whose smiles and coquetted actions told me that a wedding was on hand. Mr. Davis and I paid our bills and bent our course for Mr. Brame's. The latter's conversation indicated an informed gentleman and Christian. After tea it was agreed that if Mr. Davis would leave his valise he (Brame) would send us to Grenada on two horses, accompanied by his son. All consented and we retired that night with light hearts.

February 10, 1864

Breakfast was announced before sunrise, the horses were saddled, we bade Mr. and Mrs. Brame good morning, and off we rode, feeling that we were on our way home. As we jogged along, the day was spent in conversation, interspersed now and then with a conundrum or an anecdote. Night found us 40 miles from West Point and we took up for rest at a residence in the fine hills of Choctaw county. The lady of the house began at once inquiring the news, saying that the South was conquered and that we had better give up the struggle. Mr. Davis and I began laying before her the promising day of victory and success, and before we bade farewell the next morning she thought the Southern cause in better condition than she did the evening before.

February 11, 1864

Before the luminary of the day shook his locks over the eastern horizon, I was up at the horse lot looking after my mount. We ate a hearty breakfast, paid our bills, and set out for Grenada. The country through which we passed was lonely and the winds sighing through the pines

32

added to the general gloom. At sunset we reached Grenada where, before I had dismounted, Mr. John King pursued me down the street telling me that he had two mules for me to ride back home. I replied that I had a horse for him to ride back to West Point; so fortune had favored both of us. Davis said I was the most fortunate man with whom he had ever traveled and that he regretted to part with me. I told him that I attributed my success to my faith in God and my constant prayers for His blessings.

February 12, 1864

Learning that the cars would not leave Grenada for Oakland for two days, Monroe (the negro boy) and I started on our journey of twenty-five miles on foot to the place where there were two mules. Monroe attempted to pilot me through a near route to our animals, but before we had traveled many miles he had me in a canebrake in the Yalobusha bottom without a vestige of a road to lead us from our bewildered condition. After working my way through the cane like a rabbit hiding from the pursuing hound, we discovered a road to which we gladly kept. Arriving at a house I went up to it with-the intention of hiring horses to convey us to my mules. Found the farmer spaying pigs and I made my wants known. He refused to rent me his horses, but while I was resting my wearied legs I was using my tongue, and in a few moments the farmer said he would send his son with me ten miles. The horses were soon saddled and we made good time for 12 miles, for which I paid him, $6. The negro and I then dismounted and continued our journey on foot. After plodding for more than seven miles we reached a place where the mongrel animals were located and with no tardy motions we mounted ourselves and

33

after dark hauled up five miles west of Charleston.

February 13, 1864

Early in the morning we were fed and equipped to try the mud of the Mississippi River bottom. The first ten miles was muck and water so deep that our mules struggled to extricate their sharp hoofs from its sticky tenacity. By noon, greatly fatigued, we had reached the Tallahatchie River. which had double interest for me from the fact that twelve months prior the Yankee gunboats and transports floated on its narrow bosom. I rode eight miles down the stream, on the banks of which were many beautiful and fertile plantations. The Abolitionists had stolen from these farmers many negroes, but the people were still in affluent circumstances. We crossed the river and made good time until sunset, when we halted at a large plantation and found the gentleman and lady agreeable and polite. At night I heard some artillery firing and was somewhat alarmed, fearing that the Yankees were making a raid.

February 14, 1864

After enjoying a hearty breakfast of ham, butter, and milk, I handed the farmer a note of Confederate money to pay my bill, but he remarked, "I do not charge soldiers." This was the first service that I received on my route for which I did not pay two prices. The road lay on the banks of Cassidy Bayou and was generally dry. Two hours before the sun went down I had made 36 miles and dismounted at General Forrest's plantation where his mother-in-law and brother-in-law, Mr. Montgomery, live. The ladies let me have a yoke of oxen to drag a "dugout" a mile and a half to the river, and long before night prepared supper for my special benefit so I would not cross the river with an empty stomach. "Bless the ladies" said my heart. But when I had thanked them and bade

34

them farewell and was about driving off, the two negroes who were to steer my barque over the turbid waters of the Mississippi "backed out," and I was forced to return to the house and remain for the night. But I was determined to see my wife and children even if obstacles rose mountain high.

February 15, 1864

The morning was dark and the pelting rains poured down upon the earth. Mr. Montgomery nobly proposed to ride through the rain 10 miles to aid me in crossing the river. We reached Mr. William King's after twelve, but so soon as we could warm we were invited in to dinner. Arrangements were made with a neighbor to put me over, but after standing on the banks of that broad stream at a late hour in the night, and becoming thoroughly saturated with the leaking clouds, I had to ride three miles back to Mr. King's for the night. Ten days of my leave of absence were gone and I was not yet on that fearful stream. Oh, how precious time was to me!

February 16, 1864

The rain this morning was still falling. I went to see the ferryman, who consented to set me on the "other side of Jordan." We walked two miles to where his skiff was hid, but to our great chagrin there was a steamboat two miles below. ‘Two hours passed and there she lay anchored in the middle of the stream. Whether she was wooding or repairing her machinery we could not conjecture. Three more steamers came and went, covered with Yankees, but the anchored boat moved not. The ferryman's patience being at an end, he said that if the boat did not leave in half an hour he would cross me and run the risk of being fired at by her. This pleased

35

me and when the time had expired I demanded compliance with his pledge. Enough said; into the barque we hopped and he rowed sailorlike for the Arkansas shore. She touched the western bank all safe, and I paid him $5 for his trouble. I then set out alone on foot for the levee and called at Mr. Hewie's to learn if there were any Abolition raiders in the vicinity. Learning that there were none, I made good speed to Ike Alison's, six miles away, where I arrived before dark. I tried to hire a horse but they were all in the cane; so I continued my journey to the next house, a widow's, where I ate a snack and then mounted the top side of an Indian pony with a boy fifteen years old as a guide.

After making four miles in the dark, I saw two dark looking objects approaching me on the levee. I attempted to escape into the cane but was hailed and ordered to halt. There being a large log almost as high as the pony's back on one side and the levee on the other, I saw that to escape was impossible; so I halted. They called to know who was there. I answered, "A friend!" "What is your name?" I replied: "Captain Key." I asked who they were, but they gave no answer. I remarked, "I am a Southerner." They replied, "All right, if you are a Southerner, ride up on the levee." I rode up and as I approached I saw two revolvers drawn on me, glittering beneath the moonlight. I remarked, "Gentlemen, I am unarmed." Their pistols were lowered from my breast and I was delighted to discover that one of them was Captain Thomas Casteel. A few words passed and we parted. My pony being jaded when we arrived at Mrs. Mat Ward's, I obtained another horse and we made railroad time until we reached Big Creek. The bridges having been burned I would have to cross in a skiff and

36

and swim our horses. I offered some boys a liberal price to put us across, but they would not leave warm beds at that late hour. So for the night we had to content ourselves with the trip we had made, and called on Mrs. Hudson to allow us to sleep in her house for the remainder. The Yankees had taken her husband and sent him to Alton (Illinois), as a prisoner.

February 17, 1864

I arose early and made a fire for Mrs. Hudson, fed my horse, and prepared myself for eating. Having satisfied my appetite, I bade my friends adieu and set forth to try my luck in crossing Big Creek. Here I paid off my guide and he turned homeward with the two horses, leaving me on the bank of the stream yelling for someone to bring the canoes to this side. After I had bawled until I was hoarse, two men rode up on the opposite side, took off their saddles, and drove their horses into the rolling waters. I caught the animals when they reached the shore and the men came over in a dugout; then I gladly hopped into the boat and rowed to the other shore.

I had not gone half a mile when I discovered an old gentleman riding from me down the road. I hailed him, but seeing that I was in soldier's costume and fearing the Yankees he refused to halt. As I approached him I discovered that it was an old acquaintance by the name of Dr. Des Prez, who informed me that the Federals were in the neighborhood and that my house was surrounded by them. This news bore like an incubus upon my hopes and heart. I walked five miles to the Doctor's where I was kindly received and did justice to a good dinner. After dinner the Doctor escorted me down to Frank Lightfoot's and as I approached the house the children gave

37

the alarm that a Federal was coming. As I walked into the yard, Mr. Lightfoot met me and knowing me invited me in. Here I saw several old friends and a half dozen men on their way to attack the Federals, then in the vicinity of Indian Bay.

I waited until dark before I pursued my journey. Mr. Lightfoot sent me three miles, from which point I preferred to walk through a nearer route, knowing that if the Yankee cavalry were on one of their raids I could dodge into the woods before they could discover me. The night was cold, and as I waded through the "slashes" the water would freeze on the tail of my overcoat, which would dangle against the tops of my legs, creating a constant noise. To Prevent this from drowning out the sould of advancing Yankees, I halted every few hundred yards, and so still was everything that I could hear only my own excited and anxious heart beat. Seven miles to walk and numerous sloughs to wade were, however, slight obstacles then, when I was that near my good and loving wife and three little children whom I had not seen for twenty-two months. On I urged my way, nothing breaking the silence that reigned in the towering forest except the almost human hoot of the owl.

The moment my eyes fell upon the house which I supposed to contain those dearest to my heart, thousands of emotions mingled with many fears sent the blood thrilling with double velocity through my veins. Though it was a late hour, I could hear the negroes talking. Taking a circuitous route I reached the rear of the. house and knocked at the door before I was discovered. A voice from within inquired, "Who's that?" I answered, "Thomas Key." A servant opened the door and as I stepped in, expecting to find Mrs. Judith Lambert and Mrs. Key, I encountered a Mrs. Wiggins who, thinking I was a

38

Federal, would not inform me but directed me to the negroes, and, as she afterwards told me, was so suspicious that she sent a servant to watch me. I went to the cabin of a faithful servant named Wash, and called him to go and show me where my wife lived, as I had frightened Mrs. Wiggins so badly that I did not wish to suprise my wife.

Wash knocked at the door and called Mrs. Key, asking her to open the door a moment. My wife answered and began calling Cousin Jane, believing that the Abolitionists had come to search the house for Rebels. To keep her from being alarmed I said, "Nancy, open the door." Knowing my voice she exclaimed, "Oh mercy!" and ran for the door, turning over rocking chairs and other obstacles. But when it was opened she seemed to hesitate to approach me, thinking she might be deceived. It is useless to try to describe the meeting of two hearts that loved like ours. A candle was lit and I went to the beds and kissed my two youngest children, who were sleeping. The eldest, Julia-about seven years of age-was soon up to see her "Pa." My wife told me that the Federals had left the plantation since sunset and that they might return before day or before early breakfast; also that 17 of Captain Casteel's men had fired into 20 Federals two miles from the house, wounding one and taking five prisoners. I was in hopes that this would cause them to leave the neighborhood. However, I concluded that it was unsafe to remain all night in the house, but since it was now midnight and I extremely fatigued with the night march, I concluded to sleep two or three hours and then leave for the woods.

I lay down, but my wife had so much that had transpired since we separated to relate that I was too interested to sleep. Among other things she

39

informed me that a man who arrived at Helena on a steamer said he "saw Lieutenant Key wounded on the battlefield of Perryville," and that he, Key, told him before he died that he had a wife and three children in Helena. This threw a pall of sadness over her heart and for ten months she wore mourning for me, believing that it was all true. Her health under this strain grew ill, and she had become emaciated and almost a shadow. After the return of General Bragg's army from Kentucky, and after I had passed through the hail storm of canister at Murfreesboro, I found an opportunity to convey to her a letter which she received in August, 1863. The sight of my familiar handwriting undeceived her and she says that she wept like a child over my letter, which had proved that I was still living. Her heart was relieved and was cheered with the hope that she would see again the one who, she thought, had so long lain mouldering on the battlefield.

She related to me many of the events of the Battle of Helena, telling how the Yankees hid behind the levee while she, a woman, remained in her house with cannon balls bursting around and over it. General Prentiss , 4 she informed me, had prepared to destroy his stores and was on the eve of surrendering the garrison when General Brice retreated. General Buford5 having deprived her of two of her rooms, she determined to move to Monroe County on the place of Mrs. Lambert, her aunt.

To be continued...

40

FOOTNOTES

1See OFFICIAL RECORDS OF UNION AND CONFEDERATE ARMIES, Series 1, Vol. 30, pt. 2, pp. 140, 154, 158, 176077, 183. Cf. Key's own report of the battle, ibid., pp. 186-87.

2cf. ibid., Series 1, Vol. 31, pt. 2, p. 750.

3Just one week later, Sherman's army (of which Robert J. Campbell was a member) was to march into Meridian and begin wrecking the city.

4Major General Benjamin M. Prentiss.

5Major General Napoleon B. Buford.

41

42

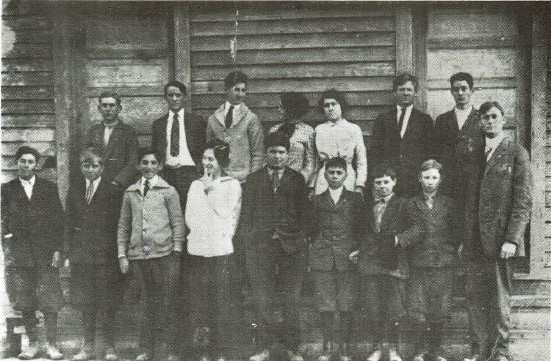

TRENTON, PHILLIPS COUNTY, ARKANSAS

SCHOOL PICTURE TAKEN ABOUT 1915

Contributed by Betty M. Faust

Front Row, left to right: Edwin Bean Hicks (1898-1960), Bean Harrell, George Seeman Goldsmith, Hazel Hall (living in 1982), Jack Harris, Jim Tom King, Raymond King. Roland King.

Back Row: Fitz Bernard, Bud Kendall, Milton Washington "Pete" Goldsmith, Bob Kendall (female), Rose Porter, Burl Jenkins, Leonard Smith and the teacher Chester Terrell. The teacher was a brother of former Arkansas Governor Terrell.

This picture is from the collection of Mrs. E. Bean Hicks of West Memphis, Arkansas.

Most of the students were identified by Miss Mable Brown of West Helena.

43

From the HELENA WORLD, May 15, 1901

CHAPTERS IN PHILLIPS COUNTY HISTORY

CHAPTER IV

by

Major S. H. King

The stores in the arsenal were turned over to the state, and the companies dispersed. The Yell Rifles boarded their boat and were soon back in Helena, where the boys, the captors of a U.S. arsenal, were looked upon as heroes, and no doubt began to consider themselves great soldiers, and such they were; and how soon and bravely were they to prove themselves. The capture of the arsenal was resistance to the United States government, and the sentiment in favor of secession soon became almost unanimous. Phillips county, whose company was the first in the expedition to capture the arsenal we may be sure was enthusiastic for withdrawal from the Union.

The members of the Yell Rifles and the other Phillips county companies were not left to pursue their wonted occupations very long. In March the state authorities issued a call for troops to defend the state. The Yell Rifles and Phillips Guards promptly responded and about the first of April '61 were ordered to Mound City, 6 or 7 miles above Memphis on the Arkansas side. With high hopes and brave hearts our boys bade farewell, thinking that in a little while they as victors and heroes would be welcomed home again. But how many were destined never again to dwell amid the old familiar scenes, and those who came back after long years of strife returned in gloom and defeat to ruined and desolate homes. Before the Yell Rifles left

44

Helena a great rally was held and a beautiful flag was presented to the company by the ladies of Phillips County.

While the troops were at Mound City a regiment was organized and Captain Cleburne of the Yell Rifles was elected colonel. Here the regiment remained about three weeks and from morning till evening it was drill, drill, drill; until the heroes who had such a pleasant trip when they captured the arsenal began to think war was hard work, and this impression was deepened when the boys were ordered to unload a steamboat bound to Cincinnati, loaded with salt, Sugar and molasses, that had been captured. They had never done such work as that, but they fell to with a hearty good will and the task was soon accomplished, though many a blistered hand was the result. From Mound City the regiment was ordered to Bearfield's Point, some twenty miles below the Missouri line. After an encampment here of three or four days, the soldiers were aroused one night with orders of "Strike tents, the Federals are coming. Get on the boats." Great was the confusion produced, some of the men rushing without dressing to the river, some seizing guns, and none understanding what was meant by "strike tents."

Colonel Cleburne soon appeared and when he had allayed the excitement it was learned the confusion had been caused by the arrival of General Bradfield, commander of the militia of Eastern Arkansas, who, instead of communicating his order to Colonel Cleburne, had sent runners through the camp with the above orders. This aroused all the Irish of Colonel Cleburne and he summarily put a stop to the embarking of the troops until he had consulted with General Bradley, who was on the boat. It must have been

45

a stormy consultation in view of later events, but the troops were ordered to come on board, and they moved down to Fort Pillow on the Tennessee side.

Next morning, soon after the arrival, our colonel proceeded to put our general under arrest. For this purpose he sent to the general's boat a detail of men who preferred to obey the colonel than any one else, and put the general under guard. Lieutenant Colonel Patton strenuously objected to any such proceeding and interfered so much that Cleburne was sent for. When he arrived he gave the lieutenant-colonel to understand that he was commander, and if the lieutenant-colonel didn't shut his mouth he too would be put under guard. Cleburne and Bradfield then had an interview, and the General was sent under guard to Memphis that afternoon. The regiment thus freed from the Bradfield impediment was then under the command of Cleburne, and began fortifying the place.

Soon the measles broke out in the camp and many of our Phillips county boys experienced another phase of army life--sickness without the ministration of tender and loving hands. The regiment remained about three months at Fort Pillow, and then was ordered on boats to be taken down the Mississippi and up the White and Black rivers to Pocahontas. During the passage down it was known the boats would stop a few hours at Helena, and we may be sure our boys had not failed to warn their families and friends of that fact, and when at last the dear old town was reached, what a crowd was there to greet them. What joyous, happy meetings and how short those few precious hours. Friends and connections from all over the country had come, and had come, bringing boxes of good things to eat, cooked at

46

home, and clothing enough for a year, so when the boys at last had to go it was with many mementoes of loved ones left behind. And how few dreamed as the Yell Rifles merrily floated down the broad old river that day that its company, the pride of Helena, had gone from it forever.

But the soldiers on the boats had little time to think of home. There were few firemen, and a soldiers' detail had to take their place, fire and load on wood. Little cooking had to be done, but the boats would stop once a day to let the men go ashore and make coffee or fry their meat. At Jacksonport everything was transferred to smaller boats to make the ascent of Black River. Finally Pocahontas was reached, and the march to Pittman's Ferry was begun. This was another phase of war our boys were inducted into for the first time. When the orders to begin the march were given they had to store away many of their boxes to await the wagons, but they loaded themselves up with a full supply of good things from home. However, but a few hours of the march had passed until the soldiers began to think they would have no use for quite so much and to leave first one article and then another on the road. By the time the destination was reached most of the articles the men had were thus deposited, and it was a weary, foot-sore company of soldiers who needed no tents that night, but lay down in the woods on the bank of the river and slept the sleep of the exhausted. Here it was, at Pittman's Ferry, that these first companies of Phillips county boys ceased to be state troops and became soldiers under the Confederate states government, and were soon taken from Arkansas.

***

47

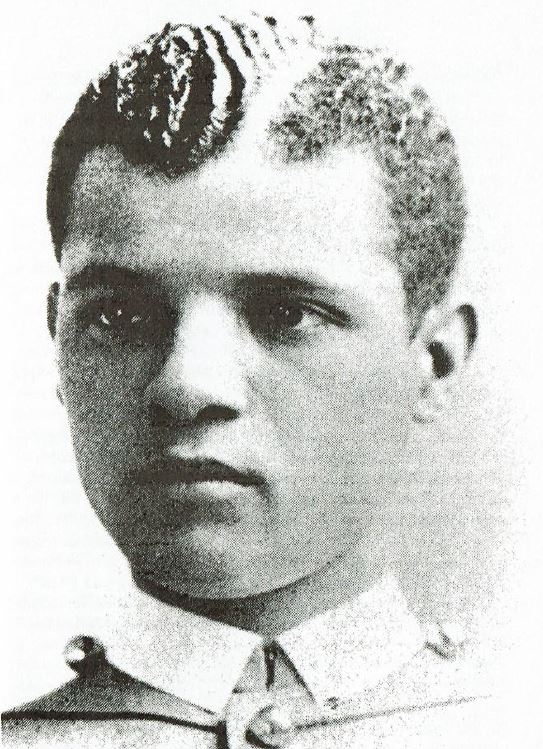

John Hanks Alexander of Arkansas: Second Black Graduate of West Point

By WILLARD B. GATEWOOD, JR.*

History Department, 12 Ozark Hall, University of Arkansas,

Fayetteville, Arkansas 72701

CONSPICUOUS AMONG THOSE PRESENT at the commencement exercises at the United States Military Academy on June 11, 1887, was a tall, stately black woman from Helena, Arkansas. A former slave, Frances Alexander was a proud woman of such regal bearing that a life-long white acquaintance thought that “her people in Africa must have been of the royalty.” A widow for sixteen years by 1887, Fannie Alexander, as she was generally known, had traveled to West Point to witness the graduation of her son, John Hanks Alexander, the second Afro-American to complete the course of study at the academy. According to reporters present at the ceremony, the applause received by Francis R. Shrunk of Pennsylvania, who ranked first among the graduates, was “as nothing compared to that thunderous hand-clapping awarded colored cadet Alexander” as he stepped forward to receive his diploma from General Philip Sheridan. For Fannie Alexander, it was a moment of “great pride and joy.” Ranked thirty-second in a class of sixty-four, the newly commissioned second lieutenant was a strikingly handsome young man whose trim fitting gray uniform accentuated his muscular litheness and whose “majestic carriage” resembled that of his mother. Following the graduation exercises, Fannie Alexander returned home to Arkansas, and her son reported for duty with the Ninth Cavalry at Fort Robinson, Nebraska. 1

*The author is Alumni Distinguished Professor of History at the University of Arkansas. This article won the Violet B. Gingles Award for 1982.

1 New York (N. Y.) Freeman, June 18, 1887; Cleveland (Ohio) Gazette, June 18, July

48

ARKANSAS HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

John Hanks Alexander was a member of an extraordinary black family whose experiences scarcely conformed to the stereotyped view of the slave family in the delta of Arkansas. Both of his parents, described in the census as mulattoes, were natives of Virginia. His father, James Milo Alexander, who was born on February 7, 1815, was a slave apparently owned by Lawson Henderson Alexander. A North Carolinian, Lawson Alexander married his cousin Lucy Jane Alexander of Virginia. Since Virginia was the birthplace of the slave James, he may well have been part of Lucy Alexander’s dowry or inheritance. At any rate, early in the 1830s Lawson and Lucy Alexander migrated to Arkansas and settled on a sizable plantation in St. Francis County where the young male slave lived for more than a decade. Lieutenant Alexander's mother, Fannie Miller, who was born into slavery near Wytheville, Virginia, had been acquired along with her mother and several brothers and sisters by Colonel Abijah Allen, a large planter and slaveowner who also resided in St. Francis County at Allen’s Landing. It appears that at some point Fannie was purchased or somehow acquired by the Alexander family whose plantation was near that of Colonel Allen. “At an early age” Fannie, a house servant, married James Milo Alexander, the coachman of his owner. Their first child, named for his father and called Milo, was born about 1844.2

The death of Lawson Alexander two years earlier significantly altered the lives of the slave couple. The absence of records makes it impossible

2, 1887; see also Chicago (Ill.) Tribune, June 12, 1887; Memphis (Tenn.) Daily Appeal, June 12, 1887; New York (N. Y.) Times, June 12, 1887; the reference to Fannie Alexander’s background is from Margaret R. Ready, “‘Tante’s’ Family History, Phillips County Historical Quarterly, XVI (March 1978), 13.

2 Ready. “'Tante’s Family History,” 3-5; Funeral Oration by James M. Hanks, typescript copy, Alexander Family Papers (Huntington Library, San Marino, California); Manuscript Census Returns, Tenth Census of the United States, 1880, Phillips County, Arkansas, Population Schedule, National Archives Microfilm Series No. T-9, roll 67, p. 244, seen at Arkansas History Commission, Little Rock, Arkansas, cited hereinafter as Tenth Census, 1880, Phillips County, p. 244. On Abijah Allen see Robert B. Walz, “Arkansas Slaveholdings and Slaveholders in 1850,” Arkansas Historical Quarterly, XII (Spring 1953), 52; James and Fannie Alexander legalized their marriage on November 11, 1863, see Phillips County Marriage Books, “Trans-1,” p. 378, microfilm copy (Arkansas History Commission). The Huntington Library has graciously granted permission to quote from its Alexander Collection.

49

JOHN HANKS ALEXANDER OF ARKANSAS

to ascertain precisely the sequence of events, but it appears that two of the planter’s children, Mark W. Alexander, who became a prominent attorney in the rivertown of Helena, and his sister, Nancy, who married J. S. Deputy, a well-known physician in the same town, took a special interest in the slave family. Clearly the status of James and Fannie Alexander was that of favored slaves who enjoyed extraordinary privileges that set them apart from the masses of slaves who toiled in the cotton fields. James learned to read and write. Fannie learned to write, but an acquaintance of many years reported in 1895 that she wrote “with difficulty; nearly all her writing is done for her…” Fannie’s mother, Arena Miller, a slave, could write and apparently did so without difficulty. 3

Sometime late in the 1840s James moved to Helena, leaving his wife in St. Francis County. In Helena4 he enjoyed the protection and support of Mark Alexander and Nancy Alexander Deputy who by that time were probably his owners. He opened a barbershop in the town which in time became a thriving establishment whose clientele included the most prominent white citizens of the city. At least as early as 1849 James Alexander was advertising in local newspapers. As his barbering enterprise prospered, he employed additional barbers and periodically relocated in more spacious quarters near the heart of the city. By the early 1850s his establishment included a stock of perfumes “of every description,” soap, toilet articles such as tooth and hair brushes, cigars, and even men’s apparel. Alexander not only worked long hours for six days a week, usually from five in the morning until eleven at night, but he also made house calls by appointment. 5 In an advertisement in a local news-

3 Ready, “'Tante’s Family History,” 4-7; Helena (Ark.) Southern Shield, January 15, 1842; Affidavit signed by Robert Wilson, May 9, 1895, and attached to Declaration for an Original Pension of a Mother, June 14, 1895, Pension Files (National Archives, Washington, D. C.); Arena Miller to James M. Alexander, April 6, 1859, as well as the letters written by James M. Alexander, dating from the early 1850s in the Alexander Papers.

4For an account of antebellum Helena, see Ted R. Worley, “Helena on the Mississippi,” Arkansas Historical Quarterly, XII (Spring 1954), 1-15; Howell and Elizabeth Purdue, Pat Cleburne: Confederate General (Hillsboro, Tx., 1973), 26-62, which includes information on Cleburne’s association with Mark W. Alexander in Helena.

5 Helena Southern Shield, April 28, November 10, 1849; April 6, May 4, 11, 25, July 20, August 3, 17, 24, September 21, October 12, November 16, December 14, 1850; January 25, February 8, 1851; March 19, 1853; Helena (Ark.) Democratic Star, March 15, 1854; James M. Alexander to Fannie Alexander, ? 1854, Alexander Papers.

50

ARKANSAS HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

paper in March 1854, he announced the opening of a new and larger “shaving Saloon”:

Jim would beg leave to inform his old customers generally that he is as polite and accommodating as ever and is always to be found at his shop on Ohio Street in Drs. Deputy’s and King’s new offices, unless professionally absent, where he is prepared to execute with neatness and dispatch, all the various branches of his business, such as shaving, shampooing, hair, whisker mustache and eyebrow dyeing. Forty minutes for dyeing whiskers, 1 hour for dyeing gentlemen’s hair and 2 hours for dyeing ladies’ hair. The public may rest assured that this is ample time for the magic transformation. No charge unless satisfaction is given. He also has on hand a large assortment of perfumery which will be sold low for cash.6

In 1857 Alexander “at no inconsiderable expense fitted up a neat clean and tasty Bathing Establishment” with hot and cold baths “utilizing rainwater exclusively.” 7

Despite his success as a barber, Alexander longed to be united with his family. His tender and affectionate letters to Fannie were filled with inquiries about members of the family and with references to his long hours of work and strivings to lead a virtuous life. 8 “Dear Frances,” he wrote in 1851, “you must talk with our little son about his father. Try and not let him forgit [sic] me. You must make him say his prayers every night before he goes to bed. You must try and raise him obedient to everybody and especially to his mistress and master.” 9 In 1853, shortly after a visit with his wife and new son, Trigg, he again expressed his desire to have his family with him in Helena. 10 The following year, after the birth of Glenn, a daughter, Alexander wrote his wife: “I want to see you so very much, dear Fannie . . . I do think it is so very hard that we

6 Helena Democratic Star, March 22, 1854.

7Helena Southern Shield, June 27, 1857.

8See especially letters from James M. Alexander to his wife, Fannie, dated September 6, September 18, 1851; September 7, 1853; ? 1854; January 5, 1859, in Alexander Papers.

9James M. Alexander to Frances Alexander, September 6, 1851, Alexander Papers.

10 James M. Alexander to Fannie Alexander, September 7, 1853, Alexander Papers.

51

JOHN HANKS ALEXANDER OF ARKANSAS

should be sepparated [sic] in this manner, but Dear Wife, I am not living in [a] world as those that have no hope. . . .” 11